All comments come from interviews conducted by the author.

Bright and early on the morning of January 24, 1848, James Marshall walked along the shore of the channel near his mill in Coloma, California, and fished out two shiny pieces of mineral. Upon examining them, he retrieved a few more pieces and hurried back to Sutter's Mill, the business he owned and operated. The employee working the mill wheel asked what Marshall held in his hands.

"Gold," Marshall answered.

When Scott expressed disbelief, other members of Marshall's workforce put the mineral to the test, banging on it with a hammer and boiling it in a solution containing lye. They reached the same conclusion as Mr. Marshall. He had found gold.

Over the next several months, trade ships sailing out of California carried the news, information their most precious cargo. Word traveled even faster through the United States. Beginning in the early spring through the end of the year, people poured in from all corners of the world. Oregonians traveled south in search of their fortune. Anyone coming from the east coast had to sail over 18,000 nautical miles or, alternatively, set sail for Panama, disembarking on the east side before taking mules and canoes through the jungle to the west, where they boarded a ship due for California.

From left to right: John Carmack, Kevin Cloud, Adrian Carmack, John Romero, Tom Hall, Jay Wilbur.

In 1849 alone, more than 90,000 forty-niners—so named because of the year they arrived—had made the journey to California. Not all hailed from the United States. Latin Americans traveled from Mexico. Asian merchants and gold hunters took ships in pursuit of Gum Sum, or "Gold Mountain," the Chinese appellation for California. Danger loomed over every route: sickness, Storms out at sea, precipitous mountain trails.

Those who made it enjoyed a period of prosperity, especially in California. The population explosion ballooned the economy. Merchants set up shop in San Francisco, roads were paved, schools and homes erected, and church bells rang. Industries were born.

Marshall had not been fated to discover gold in the channel near his mill. He did not go looking for it, nor dream of chancing upon riches. It was just there, ripe for the taking.

There are parallels between the story of id Software and James Marshall, and the California Gold Rush and the panoply of groundbreaking first-person shooters released during the1990s—regarded by many as the genre's golden age. The creators of Wolfenstein 3D, Doom, and Quake weren't trying to get rich, nor were they interested in pivoting to meet the demands of a capricious and transitory marketplace. They just wanted to make games they wanted to play, and became pioneers fueled by a passion for games and countless bottles of soda and extra-large pizzas.

Before they architected virtual worlds in which millions of players could kill Nazis, brandish big fucking guns, and skewer Shamblers with nine-inch nails, id Software's perpetually tiny team created 2D side-scrolling games with technology which, like the gold embedded in the channel by Sutter's Mill, was just there, a rich vein waiting to be tapped.

Id Software simply got to it first. From that moment forward, everyone else followed.

What follows is an oral history of id's history from their first 2D side-scroller through the release of Doom in December 1993, told by some of the pioneers who lived the story as well as other developers and industry pundits who wrote chapters of their own along the way. It is by no means a complete account. Rather, this oral history is intended to chart a rough outline of the history of id Software and the game designs and technology they appropriated—and later created—that have ensorcelled and inspired imitators and fans.

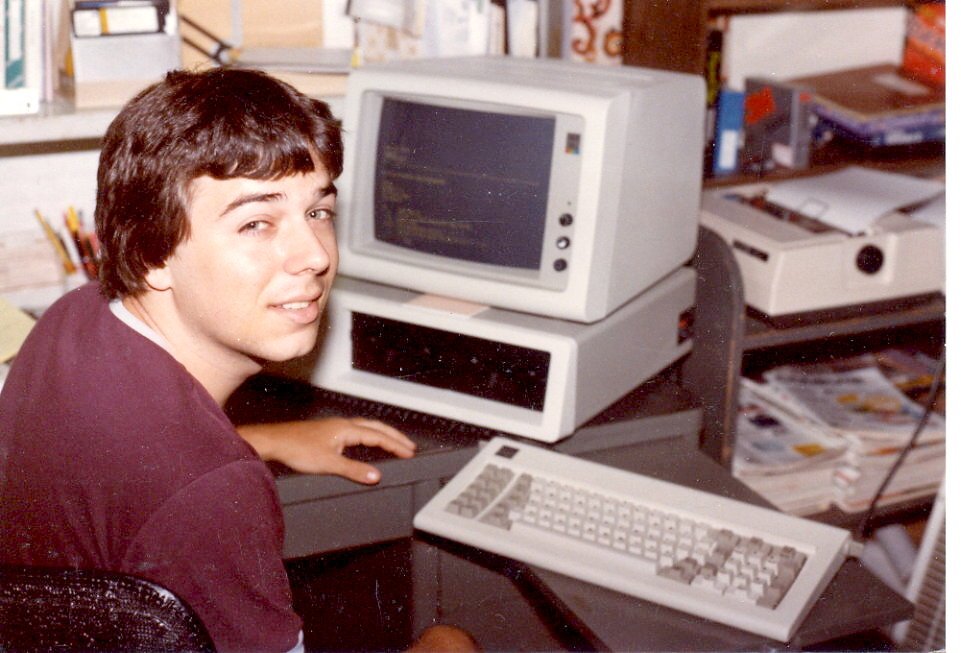

Scott Miller's first IBM PC. (Photo Credit: 3DRealms.com.)

1990: Dangerous Dave in Copyright Infringement

Almost overnight, the popularity of Super Mario Bros. made two-dimensional, smoothly scrolling platformers the norm on the Nintendo Entertainment System in late 1985, when the Japanese company's boxy console appeared in limited quantities in New York City. On the PC, such technology was considered impossible. Platform games existed, but they were set on a single screen, like Nintendo's Donkey Kong. When players hit an edge, the screen faded, and a new environment was loaded into memory.

Tom Hall, a game programmer working at Softdisk magazine in Shreveport, Louisiana, played a big part in helping the PC catch up to consoles when he met the acquaintance of new hires John Romero and John Carmack, programmers who were equally fervent about programming games .

Elsewhere, a fellow entrepreneur by the name of Scott Miller had taught himself how to program games in BASIC, and created a series of adventures known as Kroz. Each Kroz game exhibited text-based graphics drawn from letters, numbers, and special symbols. Though rudimentary, the Kroz games were easy to sit down and play. All Miller needed was a market through which to sell them.

SCOTT MILLER [founder, Apogee Software]

It's funny: through high school, the only time I got a grade less than a 'C' was my computer science class. I got a 'D' in it. I think the issue there was, someone donated a computer to the school. It was a Wang 2200, and very PC-like. It had a built-in floppy drive, built-in keyboard, built-in screen. It was really ahead of its time, looking back, but the teacher didn't know anything about it. It was his first computer.

TOM HALL [co-founder, id Software]

I graduated from college with a BS in computer science and prepared to get a 'real job.' I did a bunch of interviews, they liked me, then I did plant trips, as they were called back then; now it's just 'flying you out for a second in-person interview.' They all went well: IBM, Gould, and such, but they all said at the end of the interview, 'We like your resume, we like your skills, we like you. Just one last question: is this what you really want to do?'

And I flew home and thought. And the answer was, 'No, this is boring, I want to make games, however I can.'

SCOTT MILLER

I walked over to the lab and saw what they were doing, and I thought, 'Oh, okay. This makes the computer kind of interesting.' I started to look at these programs that people were typing in, and that's how I taught myself BASIC. I started typing them in and started to modify code to make the games more interesting. It almost became an obsession, like, 'If I'm going to learn this, I'm going to learn it inside and out.'

TOM HALL

I started working at Softdisk as an assistant editor, working for Jim Weiler. He was a great boss. It was super hard work for little pay, but boy, was it a great training ground. Basically, Softdisk was an Apple II 'magazine on disk' or a 'monthly software collection.' So we'd write eight to 10 little utilities, games, applications a month, often just sprucing up submitted programs. We worked like hell to blast out that much content every month.

SCOTT MILLER

I didn't have enough time to learn during school so I'd leave a lab window unlatched. After hours I'd go back over, just crawl through the window and stay for around three hours at a time, just me and the glow of the computer screen as I typed in my games. I got to the point where I was coming in on weekends, and I finally got caught. I had to go in front of the principal, and he looked at all these programs I'd done and saw that I hadn't vandalized a thing. In fact, I was doing this really advanced programming. My computer teacher saw the stuff and said, 'My gosh, this is really advanced stuff.'

TOM HALL

Our competitor, UpTime, went out of business, so we hired good folks from there. Jay Wilbur came over, and a coder named John Romero, who'd done a number of cool games for them. He said he'd come over if he could work on the IBM PC because he wanted to learn it. Special Projects, if I recall correctly, did one-off disks, like a business app, a game collection, or something like that. I didn't work on it.

SCOTT MILLER

The principal said, 'Tell you what: we're going to give you the key. You don't need to break in anymore. But only under the condition that if the teacher needs any questions answered, you help him out.' It was a done deal. There I was, 15 years old, and I had the key to the school so I could go in and use the computer. I did that for the last six months that we lived in Australia before we moved back to the States. As soon as we got back, my first priority was to get my father to give me the money to buy a Commodore. I've had a computer ever since.

TOM HALL

When Romero came to work [at Softdisk], we kind of bonded over Apple games. We were both avid fans of all the classic games. He had Coke-bottle glasses, and liked hair metal and classic [rock] music. I did the Softdisk newsletter for a while, and took his photo for it holding a Great White CD and a classical CD.

SCOTT MILLER

In 1987, I started using shareware through online distribution. That all came about because I was trying to find an avenue to make money making [the Kroz series of] games, and the kinds of games I was making were not the kinds of games that appeal to publishers. They wanted games that were big-budget, elaborate games. Mine were more simplistic games. But when online distribution sort of became a reality through BBSes, a little light bulb went off. I thought, I don't need a publisher. I can do this on my own.

TOM HALL

Carmack was a submitter to Softdisk. He did a cool tennis game.

JOHN ROMERO [co-founder, id Software]

Michael Abrash, back then in 1990, he was a total deity to us. He was this incredible programmer who'd been working for decades and knew everything about PC hardware and assembly language, cycle timing on instructions, everything. He wrote a book called Power Graphics Programming that I had while I was at Softdisk. When I hired Carmack [at Softdisk], I gave him that book and said, 'This is everything you could possibly know about this hardware. There's nothing that's not in here.'

TOM HALL

After about three great little games (ones we didn't have to clean up like others' games), we said, hey, maybe we should hire this guy. Romero pitched Gamer’s Edge [Softdisk’s gaming disk] with Carmack, I believe. We got in a room to name it with the senior staff. I came with a bunch of names, everyone liked that one the best. It was supposed to be two games a month; eventually it became one game [every two months]. I was buds with Romero and a bit with Carmack, and they were doing the fun project at Softdisk. [I became involved with Gamer's Edge] soon after it started.

SCOTT MILLER

There were some games out there that were pretty good, but no one was making any money. I had several little games that I'd made and wanted to use to make money, so I contacted these authors and they basically said, 'If you release your game online, you won't make any money. No one's going to pay you any money.'

One of Scott Miller's fan letters to John Romero.

TOM HALL

John [Romero] did a PC update to his Dangerous Dave, which is crazy popular because it runs on really old computers. Romero gets mails once in a while from [gamers in] developing countries who love the game. John did all the graphics for the VGA game. I had planned to do a port to the Apple IIgs, but that never got done.

SCOTT MILLER

Back in the mid-'80s, I really developed an interest in marketing. I read tons and tons of marketing books. Somewhere along the way in reading these books, the idea hit me that if I release my games online like many people were doing, I'm not going to release the whole thing; that won't make any sense.

TOM HALL

We had a multi-disc CD player, so each person would get a turn to play their music. And we were all doing discretely separate tasks, so we could just go. We'd ask for various things we needed, but we were just blazing on our own stuff, then playing, occasionally tossing about ideas.

SCOTT MILLER

Instead, I would release a portion of it. That portion would serve to advertise the full product that people could buy.

A Wang 2000, the computer on which Miller learned how to program.

TOM HALL

We all played games together on the NES and PC, and we all loved Apple II games, so we were always talking about what was cool. We watched Carmack finish Sonic the Hedgehog on the Genesis. I helped Romero get through the maze before the boss in Super Mario World. It was games, games, games.

SCOTT MILLER

It was a slow start, but it became successful. People started sending me my checks, and that was really the start of the business, back in 1987. I quit my day job at a computer consulting company in 1990.

TOM HALL

Carmack had just finished the smooth-scrolling-tile trick and had a sample sprite of Dangerous Dave bouncing around over it--first time there was cool scrolling that we'd seen on a PC. That was like his first amazing hack I remember, one that let technology jump forward. Seeing that, then I looked over in the corner to the NES, which had Super Mario 3 on it. I smiled, and said, 'What if we did the first level of Super Mario 3... TONIGHT?!?' Carmack smiled and said, 'YEAH!'

JOHN ROMERO

Side-scrollers had been around for a while, and so the fact that the tech could do side-scrolling, we knew that that was going to be super impressive on a PC.

TOM HALL

So, we got to it. I started/paused, started/paused the NES, copying all the tile graphics, then grabbing them with a tool, getting them in Romero's editor, setting tile attributes, Carmack and I agreed on what meant 'solid,' what meant 'death,' what meant 'coin block,' and so on. Carmack made the little character behave [correctly]. So I painfully made the whole first level, did some sounds, did the coin graphics, made the title screen, animated the Dave character. I don't think we got any enemies in. So we did that from the evening to about 3:00 a.m., finished it, put it on Romero's desk, crashed. It was made for fun as a joke, out of pure joy and love of games. We came in the next day. Romero closed the door and said, 'I've been playing this all day. We're so out of here.'

JOHN ROMERO

That's where he got the information to do smooth scrolling. That Power Graphics book did come out in 1990, but the tech specs for EGA had been out and nobody had gone to the assembly-language level to figure out how to make stuff run fast.

TOM HALL

In the science of happiness—one version at least—there are three things that make you happy. Pleasure-seeking is short-term. But experiencing flow, where you love what you are doing for work so much, you lose track of time' and creating meaning for others, people enjoying games, are the things that make people happy long-term. And that's exactly where we were. The time working on games just flew by.

A photo taken by Tom Hall in September 1990, at the lake house in Shreveport, LA, id Software's first office/bachelor pad. In the background, John Carmack (right) and John Romero work on the Super Mario Bros. 3 demo for Nintendo. Sitting in between their computers is an NES running Super Mario Bros. 3, which the two Johns played frequently to make sure they nailed the feel of the game. To the right, a desk holds Hall’s equipment: a 386/33MHz PC running DOS, and an NES running Super Mario Bros. 3. To capture the exact look and feel of the NES classic, Hall paused the game and duplicated the artwork pixel by pixel. (Photo credit: John Romero.)

1990: Commander Keen

In a single night, Hall and Carmack harnessed aging technology to draw backgrounds that scrolled smoothly left and right. The Gamer's Edge team was over the moon and had one foot out the door at Softdisk. Their plan was to put together a demo that cloned Super Mario Bros. 3 using Carmack's smooth-scrolling tech and pitch it to Nintendo. If the Japanese developer/manufacturer wanted to break into the PC business, id would be the hammer.

Nintendo demurred. It was enjoying tremendous success with its NES and had a successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, in development to compete with Sega's 16-bit Genesis. Down but far from out, the gang at Softdisk looked for another way to split from the magazine and start their own business.

Scott Miller offered them an out, albeit from an oblique angle. Writing several letters to Romero under pseudonyms, he gushed over the Dangerous Dave platformers. Romero swelled with pride until closer examination of the letters outed Miller as the author behind nearly all of them. Miller phoned to apologize for his subterfuge and offered a deal. If Romero and his friends could pitch him a game, Miller could help them sell it using his shareware model of distribution.

SCOTT MILLER

John [Romero] sent me this disk in the mail that was this beautiful, side-scrolling demo of Mario. It looked exactly like what you'd find on the Nintendo; it was just the most amazing piece of technology I'd ever seen. So they had this technology and they didn't know what to do with it.

TOM HALL

When we couldn't do Super Mario, we talked about what to do. I said, 'I can do anything.' Carmack said, 'A kid that saves the galaxy or something.' I was so there. I left for 15 minutes, wrote the paragraph you see in the game, read it to Carmack in a Walter Winchell '40s newscast voice, and Carmack applauded. That was it.

SCOTT MILLER

It was easy to see that the founders of id were special—they were the total package. Their pre-Apogee games were fun, had impressive graphics, and had cutting-edge technology for the PC right from the beginning. When I saw their scrolling engine demo of their mock-up Mario game, I was blown away by the smooth pixel scrolling.

Kingdom of Kroz, Miller's shareware hit and the game that put Apogee on the map.

JOHN ROMERO

That's why we made Commander Keen: Nobody on the PC had made a smooth-scrolling game. Even though other platforms had smooth scrolling, the PC just didn't. When we had that, we took advantage of it and made side-scrollers to show off that tech because it was perfect for [that type of game]. We made a lot of side-scrolling games, a whole bunch. At least a dozen; probably more than 12.

TOM HALL

It was just a fanciful universe. Beyond that bit of framing story, you just want to create a consistent universe. If you create a fun to control character, and have the enemies act in a funny, consistent way, the joy is there even if you don't get into the pure context of it. But I never put so much story in that you were just waiting to get into the game. Keen 1's story is just in the menu mostly. The end uses story as a rewarding finish. And Keen 1's is a cliffhanger to get you to want Keen 2 and 3!

SCOTT MILLER

I immediately worked out a deal with them to fund their first shareware game, sending them a check for $5,000, which was nearly all the money I had at that time. I encouraged them to form a game studio and make games for Apogee to publish using my shareware trilogy model, and id was born.

TOM HALL

My mom gave me a love of cryptography. I love secret codes, puzzles, and so on. My childhood was filled with puzzles, cyphers, and such. I love that, so I made a sign for the EXIT, but I wanted it to be in 'alien language' but recognizable as an exit sign. So I drew those four characters, then thought, It would be fun to have a whole alien alphabet on signs and stuff.

It grew from there. It is just another fun secret to discover.

SCOTT MILLER

We released the first episode of the game on December 10th, I think. I remember releasing the game to all the BBSes I had partnerships with because they would feature the game on their front pages. Then I went away on a ski trip. Before I left, I put a message on my phone machine because I didn't have customer relations at the time, so I just used a message machine.

JOHN ROMERO

I think back then on a PC, because the PC had languages that were compiled like Pascal and C, people mostly used those languages. Whereas on other platforms that were 8-bit, people used assembly language and were used to messing with registers and doing everything at that level.

A Softdisk reunion held in 2003. From left to right: Tom Hall, Rhonda Reimers, Lane Roathe, John Romero, Jim Weiler, Carolyn Drain, Fender Tucker. (Photo credit: John Romero.)

SCOTT MILLER

Two days into my ski trip, I called the machine. It was maxed out. It was maybe 30 straight minutes of people placing orders. I thought, 'Oh my God.' I remember having my mom go to my house, write down all the orders, and reset the machine so it could take more orders. I left the ski trip a couple days later and immediately hired a guy to go to my house and take orders. That was Shawn Green. Shawn would come to my house and man the phone all day to take orders. In the first month, I think we made $20,000.

TOM HALL

It was really fun thinking of things that pretty quickly came to life. Sonic the Hedgehog came out and had a rotating spiky bar you run across. I surprised the guys with that by staying up and doing the graphics and setting up tile animations. Then we put it in, but with energy posts instead of spikes. We did the original trilogy so fast. It was create and go. Coming up with new ideas was fun. Like having to turn out the lights to get past Vorticons. It was just a flow of ideas. The original trilogy was a joy.

SCOTT MILLER

Once my company was associated with Commander Keen, the game became the rage of the shareware world. Not only was the game great, but we'd worked it out so that it made the authors and Apogee tons of money. Suddenly, people were calling me. Tim Sweeney sent me a demo and said, 'Hey, would you be up for working with me?' I still kick myself to this day for not working with him. He was brilliant. His game was cool and all, but it was kind of like Kroz and we were working toward getting better in graphics. Of course, Tim went on to become a big success at Epic Games.

JOHN ROMERO

Because of the PC, fewer people worked at the assembly level and didn't bother to get into graphics and things like that. Far fewer people went down to that level. Luckily, Abrash did, and we benefitted from getting his information and turning it into some awesome side-scrolling games.

TOM HALL

We got our first check for $10,000. We looked at each other and said, 'We can live on this!' It was a revelation. We could have our own company making games and making a living. The brass ring had arrived. We had to reach for it.

SCOTT MILLER

My deal with id was we were splitting things 50/50. So yeah, the floodgates open. We started releasing probably five to 10 games a year for a few years there. We were making a lot of money. Those were good times.

TOM HALL

We were just excited to make the games we wanted to play. Just the four of us working endlessly together, each in pure creation mode—tools, game, design. We were just flowing, a set of folks each doing their part to the best of their ability. No production. No design docs. Just flow.

JOHN ROMERO

When we finally got to the point where we were being recognized, there was a point at id, right [before] Wolfenstein, when I felt like we were invincible. From the company we'd started in 1990, doing stuff that no one else had done on the PC, which had been out for nine months at that point. In nine years, no one had done what we did, what John Carmack did, with Commander Keen.

TOM HALL

That should be your goal: Make yourself happy. Make meaning for others. Don't worry about the money. That's the short-term pleasure focus, and a mistake. Focus on what you absolutely love, and what would be meaningful to others. Then if the money comes or not, you made what will make you happy.

JOHN ROMERO

Going into Wolfenstein after playing around with a couple of 3D games, it was like, 'What can't we do? We can do pretty much whatever we want to do. Anything we set our minds to, we're doing it.' That invulnerable feeling was just a ton of confidence that we'll be able to do what we decide we want to do.

1991: Hovertank 3D, Catacomb 3D

The Gamer's Edge crew lived two lives. By day, they went dutifully to Softdisk's office and built games for the magazine. After work, they loaded their work computers in their cars and trundled home to set up shop and write more entries in the growing Commander Keen series. Pizza boxes piled up. Stacks of soda cans were used to measure just how long they had been glued to their monitors.

At first, they called their nascent enterprise id Software, short for 'Ideas from the Deep.' Later, they shortened the acronym to 'In Demand,' as appropriate a designation as the word's other, psychological denotation: The id, or the ego in the psyche.

With Carmack's technology in place, id cranked out 2D platformers with plenty of time to meet Softdisk's deadlines. As their game designs grew more complex, the deadlines stretched out. Their next endeavors, a pair of 3D shooters, proved their most technologically ambitious to date.

JOHN ROMERO

There were 3D games before we made ours on PC, but they were really slow, and 'really slow' means 'not fun.' If you look at LHX Attack Copter, look at the early Novalogic stuff, there were games in 3D on the PC, but they were really slow, and 'really slow' means 'not fun.' We knew framerate meant more than anything. If you have a super-fast 2D game, you'd rather play that than a slow 3D game.

SCOTT MILLER

3D games push PCs to their max ability in practically every possible way, including sounds, music, and interface. In the early days, these 3D games came closest to simulating reality, and giving you the actual feeling of being inside a game world. These early 3D games demonstrated the exciting potential future of gaming, with true immersive experiences.

Tom Hall: Battlezone was really where you first felt 3D. Skyfox, Horizon V on the Apple II. And for first person mazes, Wizardry, Ultima's dungeons and such were not smooth-movement, but gave you that sense. So, this was just all those growing up, taking that next step, literally.

JOHN ROMERO

The very first 3D thing that John [Carmack] wrote was a spinning cube in January of 1991. We finished making Commander Keen on December 4th of 1990, and we took Christmas vacations, and when we got back, we were still working at Softdisk at that time. He thought about it more, and finally, around April of '91, we were making games every few months. February and March was Dangerous Dave and the Haunted Mansion. In April, we took two months to make another game, and John decided, 'Hey, I think I want to try to make a 3D game.'

TOM HALL

It wasn't too hard, though it meant a lot of new stuff. But we were in the zone. We still used TED [Tile Editor, John Romero’s custom editing software] to make the maps, really 2D in nature. The hardest bit was on Carmack, figuring out how to get smooth movement in a 3D maze of sorts. Some of the same design principles applied. Some needed changing. Some language and mechanics and controls needed inventing. And the first forays were a lot more simplistic, and had to be finished in a month.

JOHN ROMERO

Hovertank [had] solid-filled, polygonal walls, ceilings, and floors. That was his first real 3D code, and it was the only time he felt real stress while making a game because it was hard to do. In fact, he didn't get the game done until the two months. It was just grinding constantly, trying to get 3D working, getting rid of problems like the fish-eye lens—it was his first really, really hard [project]. He got it done under deadline, and it was all him. He wrote all that code.

ROB SMITH [former editor: PC Games, Maximum PC, PC Gamer]

You have to understand what came before, which was not any of what id Software delivered. This was the emergence of 3D, which wasn’t a thing in [1991]. Or not [for any consumers except] the hardest of hardcore. So, we all entered a new market, a new environment. And it seems so odd now, but manipulating a 3D space was not obvious.

JOHN ROMERO

John wanted to make a 3D game, so it was like, 'Oh, he wants a 3D game? Let's put some design on it.' That was Hover Tank 3D. We basically had already made Catacomb 1 and Catacomb 2 for Softdisk. The idea of Hover Tank was [navigating] this 3D maze, but we decided, 'Let's do another 3D maze, but this time do texture mapping on the walls.' Because it was the third Catacomb, we called it Catacomb 3-D. Which is exactly how we named Wolfenstein.

TOM HALL

Having textured walls was a big difference from a game where a 10x10 cube was a 'tree.' The previous game was very limiting. This could convey better sense of place, for sure. And since [the world] was magic, secret walls could just blow up to reveal areas.

JOHN ROMERO

The interesting thing about texture mapping is that I was working at Softdisk in 1990 when I would periodically talk to Paul Neurath on the phone. Paul started Blue Sky Productions, which changed their name to Looking Glass later. I would talk to him periodically on the phone, and he told me that he was doing a game for a company that he couldn't tell me but I could probably guess, working with a company that was also pretty popular, and I could probably guess that.

TOM HALL

Having your hand out there in front of you made it feel a lot more personal. You were casting those spells. That really felt like the first FPS-feeling game, though Hovertank was technically first, and Wolfenstein 3D is the most well-known.

JOHN ROMERO

They had a really great 3D graphics programmer, who was Doug Church, and they were using a really great technique called texture mapping to put drawn graphics onto rendered polygons on the wall. When I got off the phone, I told Carmack, 'They're using something called texture mapping to put tiles on walls and move them in 3D.' He thought for a second, then said, 'Yeah, I could do that.' That was a whole year before we used that information. We learned about texture mapping probably around November of '90. It wasn't until November of '91 that we used it in Catacomb 3-D.

TOM HALL

I just put [the player’s hand] in there as the natural thing to do. It gave you person context, sort of body awareness, and was natural to do after Hovertank's turret. Also, it was important that you were a person casting spells, visually conveying the state of casting and readiness.

JOHN ROMERO

When you're making a game as big as Ultima Underworld, those games take years. When we made games [back then], we took two months. We put out six games in six months in 1991, in the last half of 1991. We did a lot of games that year. That's why we could get texture mapping up and out within two months.

1992: Wolfenstein 3D

With some assistance from Apogee, the id Software crew put a bow on their contractual obligations with Softdisk. At last, they were free and clear to write Wolfenstein 3D, their most cutting-edge FPS yet.

Inspired by the 1981 title Castle Wolfenstein and building on the foundation of the code that Carmack had written for Hovertank 3D and Catacomb 3D, Wolfenstein 3D originally shared much in common with its Apple II namesake, Castle Wolfenstein. Players would creep through floors of Castle Wolfenstein, Hitler's secret fortress, stealing Nazi plans and looting Nazi corpses for keys.

Romero and the others soon grew bored of sneaking through castle corridors. As Carmack's 3D engine took shape, the guys were having more fun shooting their way through obstacles instead of thinking their way around them, racing along stone corridors and killing Nazis with big, loud guns.

While Hovertank 3D and Catacomb 3D represented significant but small steps of progress for first-person shooters, Wolfenstein 3D was a giant leap forward. The game's speed, immersive aural design that put newer sound cards such as Creative Technology's Sound Blaster 16 to work, and blisteringly fast action immediately gave PC owners who had let their hardware molder ample reason to upgrade.

JOHN ROMERO

So there was Catacomb, then Wolfenstein, which we started doing in EGA mode. Then, only a week or maybe a couple of weeks into Wolfenstein, Scott Miller called us.

SCOTT MILLER

My gut feeling was that cutting-edge graphics was the way to go.

JOHN ROMERO

He said, 'Don't even waste your time on EGA. If you do this in VGA, it's going to just be the coolest, hottest game.' So we said, 'Okay! You're the marketing guy. If you say the market's ready for VGA, we're ready for VGA.'

SCOTT MILLER

I pitched the argument that while VGA [Video Graphics Array, 256-color cards] was a smaller market than EGA [16-color cards], every single person who had VGA would absolutely have to own this game because they would want to show it off to all of their friends. I still remember stating that as an argument. Not sure it was a great argument, but it made sense to me.

JOHN ROMERO

You could see your hand throwing fireballs out there [in Catacomb 3D], which was kind of lame. So, for Wolfenstein, we decided, 'Let's just put guns [at the bottom of the screen].' The funny thing about doing games in first-person like that was that our first instinct was to go third-person. But we didn't want to go third-person because that would involve too much [rendering] on the screen and kill our framerate.

TOM HALL

We recorded bad German interjections from the back of a Merriam-Webster dictionary I had, and still have. I assumed that since my sister took German in high school, I could by osmosis pronounce and be vocal coach for the phrases. Not so much.

JOHN ROMERO

Drawing a character over a 3D scene would be like drawing a whole bunch of pixels over pixels you'd already rendered, which would be a waste of time and it would hurt your framerate. We wanted a high framerate, so we decided, well, what if we don't even draw a character? Just put a gun there.

TOM HALL

The audio was so amazing. The brash sound of the chain gun is one of my favorite video game sounds. And that was important to be true to its ancestor, Castle Wolfenstein on the Apple II. Hearing 'SS' and 'Aieeeee!' in that early game was amazing. But the sonic impact added a ton. That's a big component of feel, mood, and feedback in a game.

JOHN ROMERO

It sounded great compared to nothing, because everybody was using FM Synth for all their sound effects. We were doing that as well. So when you hear digital audio, and all you've been hearing is FM Synth, it sounds amazing comparatively, but those sounds were only 11 kilohertz, as low as it gets. But that's what we needed to use because it would have slowed down your computer if we had too high of a DMA rate getting those sound samples off the hard drive and into memory.

TOM HALL

Bobby Prince made [sound effects], and we'd give him feedback if a sound seemed off, or ask for something specific we had in mind.

JOHN ROMERO

Back then, computers were really slow. We're talking 33 megahertz back then, so we couldn't afford to do 22khz [sound effects] because the whole game would have felt a lot slower. Every decision about why those games were the way they were is so they would have a high framerate and be responsive. We had to sacrifice quality in certain areas to get a high framerate.

TOM HALL

The game was made to be fast and brutal. The slow version just felt too fiddly and awkward, too many keys to press. And speed is what really made the early games sing.

ROB SMITH

My 386 SX was average—possibly below average—at the time, so you had to figure out ways to make the games play. So there were memory management programs like QEMM, and I will never forget the Qemm did not cause this error, but is just reporting it to you; error message. For gamers, that forced a rethink of our technology. And then came the 3D card revolution—much later, of course.

TOM HALL

In Wolfenstein and Doom you could blaze around a map. Quake and most other games slowed you down a lot. The faster running amps up your energy, your dopamine levels. Kind of puts you on edge and amps up everything.

1993: Doom

For many, Doom is more than a game. It's the game. Carmack's custom engine, id Tech 1, was an order of magnitude more advanced than any he had written before, enabling players to climb stairs, ride lifts, adjust lighting, and arm players with weapons that could eradicate an entire room of demons in a single blast of toxic-green plasma.

Enormous as those features were, they paled in comparison to Doom's two greatest achievements: Out-of-the-box support for multiplayer over modems and networks, and the ability for anyone to build and distribute their own levels.

First-person shooters have undergone dramatic paradigm shifts in the days since Doom was bright, shiny, and new. But even the best—Half-Life, Halo: Combat Evolved, Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, even id's Software true-3D spiritual successor, Quake—stand on Doom's shoulders.

ROB SMITH

Any time I'm asked about my favorite game of all time it's always Doom. I loved Wolf, the Apogee games, but Doom changed what a game could be.

JOHN ROMERO

Before then, everything was just 90-degree walls—cubes, basically, from Wolfenstein. When we started Doom, we were just replicating that design aesthetic, and it was just boring and garbage for probably five months. One day I finally just said, 'I'm going to solve this level problem.' I spent a few hours going nuts with the Doom tech, trying to do stuff we hadn't done before.

ROB SMITH

I haven't played it on all the formats it has appeared on—which is all of them, right?—but I hear that music, hear that growl, and never gets old.

JOHN ROMERO

I made a really neat room that ended up being in E1M2. When you go into the level, you go through the red door on your left, move down the hall that curves around to your right, go up the stairs, and there's a room that has slime in it. Go over the slime and walked onto the elevator. The elevator lowers into a really tall room that's dark but has some lights on ledges with monsters on it.

AMERICAN MCGEE [level designer, id Software]

I dropped out of high school when I was 16 due to issues at home. I then went on to become a car mechanic. At the time that I joined id, I went from being a car mechanic to working on games. I met John Carmack because he and I lived in the same apartment complex. He would come home driving a Ferrari, and I would come home covered in grease and burns, but we became friends. We started playing games together, and he started inviting me up to the id offices to work on testing their games. That eventually [led to] a job offer.

Doom's iconic box art.

JOHN ROMERO

Basically, everything made from that point on, in shooters made during the '90s, sprang from that day. Everything before that was [modeled after] Wolfenstein-style levels. All of the games—Ken's Labyrinth, Isle of the Dead, any of the numerous Wolf clones—were all simple copies of Wolfenstein. But Doom was the first engine that was capable of a more interesting world, but we were still replicating that stupid design until I decided I was going to do as much as I could with the engine.

AMERICAN MCGEE

Carmack put me in the position of answering phones for tech support. It was myself and a guy named Shawn Green—we were the entire tech support [department] for id Software.

TIM WILLITS [level designer, id Software]

I'd never actually played Wolfenstein, so for me, Doom was the first id Software game I played. I'd just gotten a new computer, which is funny because when I downloaded the shareware episode of Doom, I didn't realize the door opened [in the first room].

JOHN ROMERO

I think with modding games, you should be able to release tools that are easy to use and that keep people away from the low-level details they don't need to know, but still give them the ability to modify config files if you know how those work, and let players run their own servers.

AMERICAN MCGEE

While I was answering phones, I was also tinkering with the [Doom] editor. I taught myself level editing, and then that eventually allowed me to transition, I think it was within six months of joining id, that I transferred over to being a level designer. The first project I had maps in was Doom 2.

TIM WILLITS

I was running around for a while and I thought, This is awesome. I'll buy this game. Then I figured out how to open the door. That was a moment where my whole life changed.

JOHN ROMERO

With poor tools, it can be harder for people to mod the game. But closing the game off, and not allowing people to run their own servers, kills the potential for the game to live for a long time.

RICHARD 'LEVELORD' GRAY [level designer, Apogee/3D Realms]

For me, of course, [the ability to create mods] was life-changing. It is how I became a level designer. All of my colleagues and coworkers were educated and honed by modding and level editing tools.

TIM WILLITS

I was really fascinated by the fact I could download a level editor. At the time, it was DEU [Doom Editing Utility]. I was fascinated that I could create an infinite amount of content. I thought, I can build anything I want.

JOHN ROMERO

In the middle ground, publishers could support modding and release really nice tools for your game, kind of like the way Pinball Construction Set worked. Everybody could make pinball tables on it, and they could come on their own disks, and you don't have to know anything about programming, or format a disk, or anything.

TIM WILLITS

I had a membership at Software Creations' BBS, and there were other people who had made Doom levels and uploaded them, so I [uploaded mine]. It was really cool that people would email me and say, 'Hey, these are great. I downloaded them.' Then the id guys were looking to contract folks for the Doom II [Master Levels]. They sent me an email saying, 'Your levels are pretty good. Would you be interested in making two more?' I was like, 'This is the greatest thing ever. I can't believe this.'

RICHARD GRAY

I think [lack of mods in console games] is a horrible situation. I'm not sure it [stifles] innovation, so much as developing talent and culturing new designers.

TIM WILLITS

No one really was in that position at that time because there weren't games you could download editors for and make things, so the idea that you could create something to mod a game and end up getting you a job in the industry? That really did not exist. I was very blessed.

ROB SMITH

In the formal style of an English company, we got to work at nine and left at five or so. And noon to one was lunch, and so that meant multiplayer Doom. We were sat in a row, playing away. Then, the company had launched a PC gaming magazine, PC Action, and one of the people hired was Pete Hawley, latterly of Bullfrog, Sony, others. Pete got to go to id [to cover], I think, Doom 2. When he came back he took a week off work. Turns out he’d discovered that the id guys used a mouse instead of just the keyboard, and they schooled him.

JOHN ROMERO

The way PC keyboards are laid out, there are what's called scan lines. There are scan-line rows. You get scan codes, which are hex values for every key that's pressed. Back then, keyboards could only report two scan codes simultaneously. They couldn't do more than that. Running by holding Shift and arrows was okay because [those keys] were on the same scan line, but hitting Space [to jump] would have overwritten a scan code and you would have stopped running.

ROB SMITH

Turns out Pete had discovered that the id guys used a mouse instead of just the keyboard, and they schooled him. So he learned how to play with a mouse and in turn came back and schooled all of us. That was also defining. We’d played Wolf 3D and others with the keyboard, but Doom brought the mouse into the equation. Seems so simple today, but then, it was revolutionary.

JOHN ROMERO

That's the reason why in Wolfenstein, when you hold down MLI, that's the cheat code. The reason why it's MLI and not BNM or something on the same scan line was because keyboards couldn't read all those keys. That's why I used three scan line rows: M, L, and I. Some people thought it was ILM for Industrial Light and Magic. It wasn't. MLI for Machine Language Interface, which was the way you communicated with Pro DOS on Apple II, in assembly language.

ROB SMITH

Doom changed the game. I was writing about Gameboy games in 93, but those PC guys had their Duke Nukems and Blake Stones. But not to go into too many details about how I came to own a PC—best investment of lay-off money ever—there was a moment when I was connected, and I was playing Doom, and another player slid awkwardly into view. Suddenly, another player was in my game. This had literally never happened before. And I shot him!

JOHN ROMERO

It's kind of funny, though, thinking about it. At the point where we did Commander Keen, and reviews were coming out, and we were doing interviews with people—before that, my life was still on a rocket trajectory. I went from not knowing anything about programming to learning and learning and making and making. I wanted to go to Origin, and I got the job. I beat out four other people who were experts at a machine I didn't even know, and I beat them. It was one thing after another. I'd think, I don't know where I'm going, but I'm going up. Every step I took was taking me up toward id, and from there we continued going up.

ROB SMITH

Id was the leader. John Carmack was the founding father of this leadership. The gameplay was rudimentary—shoot demons in hell—but multiplayer changed the game. I still couldn’t play multiplayer at home. Internet services were expensive.

JOHN ROMERO

To me Doom is optimal. Quake was way slower than I like to play; Doom was super high speed. People who are used to playing Quake are used to going at half the speed. Unless they're amazing Doom players who have been playing for years, I can usually win.

ROB SMITH

I had a 14k modem at work that was state-of-the-art so I could download WAD files from CompuServe to put on the disc packaged with our magazine. Ah, the glory days before copyright and ownership, and an internet to air grievances.

JOHN ROMERO

I'm always joking around, I'm always sarcastic. That's just the way I am. But I never, ever [adopt an attitude of], 'I'm better than you.' I've never done that to anybody. I'm just so excited about making games and knowing how to do it really well. That was really the whole point of what we were doing: To continue doing what we wanted.

I did not love doing interviews, and I did not love showing off that I had a bunch of money and cool cars. It was just like, 'Yes, I bought those things,' and people are going to see that. Whenever people come to do interviews, they've heard about the cars and they want to see them, and take all these pictures of you with your cars, just perpetuating [that rock-star image]. I'm excited to show off my car because it's really cool, but the enthusiasm makes you look like you're trying to be better than everybody.

It's all enthusiasm. 'Look at what the poor kid did. He worked so hard.' That's what it was. It was just a bunch of fun. It was just fun, you know?

Doomguy sends an Imp back to hell.

Enjoying Rocket Jump? Click here to share your thoughts with other Shackers in the Chatty.