Doors and Colors

Over six years, John Carmack had proven himself one of the most brilliant programmers in the world.

He had repurposed old technologies to coax PC hardware into drawing tile-based environments that scrolled as smoothly as Super Mario games flowed on NES consoles. Pushing the envelope, Carmack had broken free of two dimensions and set players free to explore vibrant 3D worlds. Deathmatch let friends and strangers close the gap between continents and trade salutations and BFG blasts.

All those accomplishments, all that genius—until 1997, when Carmack met his match.

A door.

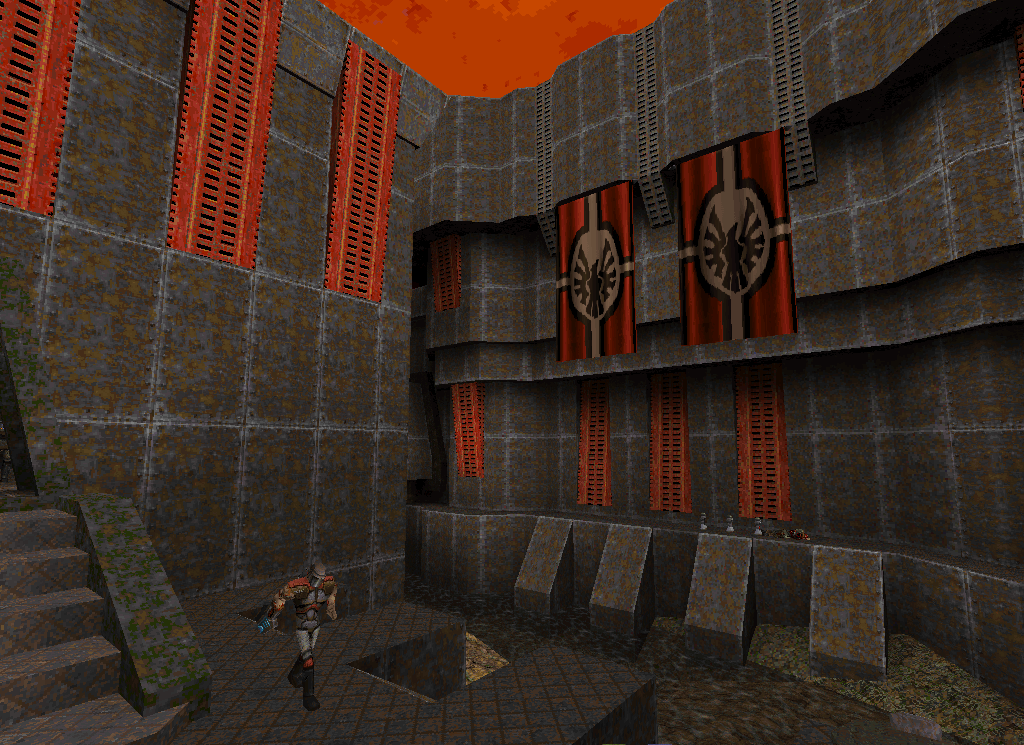

Strogg guard a door in Quake 2.

"It has always been a problem with Quake that putting a door in front of a complex area didn’t make the scene run any faster, unlike Doom," Carmack wrote in a .plan.

Following Quake's release, Carmack had run a test. He had been keeping an eye on GPUs (graphics processing units), add-in video cards with dedicated processors and memory which generated visuals more efficiently than a PC's built-in hardware. Many manufacturers predicated their GPUs on OpenGL, a set of routines capable of rendering graphics an order of magnitude more stunning than those produced by software, the paradigm used in Quake and other early first-person shooters.

Carmack took OpenGL and GPUs for a spin by writing GLQuake, a port of the game that wrapped the original source code in hardware-enhanced capabilities such as transparent water, crisper textures, and real-time lighting and shadows. GLQuake was a testbed for features Carmack wanted to include in Quake 2, but doors and GLQuake seemed unable to get along.

The problem, he explained in his write-up, was twofold. As players approached a door, GLQuake would slow to a crawl due to the complexity of the geometry being drawn and redrawn hundreds of times every second. That hadn't been a problem in Doom: Whether a door separated the player's location from a closet-sized hiding spot for demons or a sprawling cave full of monsters, id Tech 1 deftly processed sprites and pixels, pumping out environments and animated actors without missing a beat.

The second issue was that Quake's monsters could hear sounds on the other side of doors. It was a realistic but unintentional touch. Forbidding monsters penned in rooms from hearing sounds until the player opened the door facilitated better gameplay by giving players a chance to get the jump on enemies.

Carmack pinpointed the source of both problems quickly. Quake's engine employs a culling mechanism known as PVS, or Potentially Visible Set. The PVS calculates an approximation of everything players can see from their current position. When a door opens, all the data previously sealed behind it—monster positions and movement, architecture, items, projectiles such as bullets and fireballs—are added to the PVS, which labors under the increased weight.

To lessen the load, Carmack modified id Tech 2 to include an entity called areaportal. Each areaportal acts as a fence post with which programmers can demarcate areas of a map. Most are placed in doorframes. If Quake 2 detects areaportals beyond a door, and those areaportals are inactive—meaning the door is closed—nothing beyond the door will be counted as active.

Adding areaportals not only gave id Tech 2's rendering speeds a boost, it lightened burdens placed on network bandwidth as well, especially for deathmatch sessions on larger maps.

Many of Carmack's sweeping changes to id Tech 2 manifested in ways noticeable only to those with an eye for technical details. Under the hood, the engine increased support for hardware-accelerated graphics provided by GPUs by building on the foundation Carmack had laid for GLQuake. Packaging Quake 2's logic and other proprietary components in DLLs permitted modders to write custom gameplay rules for Quake 2 when it released without revealing trade secrets that id preferred to keep to itself.

Other engine upgrades benefited Quake 2's artists and level designers. The most obvious change was Quake 2's palette, which brimmed with primary colors that juxtaposed sharply with the first game's brown and metallic leanings. Also unlike Quake, the sequel's palette and texture sets facilitated the overarching goal of synthesizing gameplay, art, and story.

Artifacts, awards, and other memorabilia from id's office in Dallas.

"Going into it, we felt we had good design, which, you always feel that way. You never feel like, 'This game is going to suck, but we're going to make it anyway,'" Adrian Carmack said. "I was happy with the design direction, so the palette was decided from the get-go. There was nobody coming in saying, 'You need to get the palette done now' because someone doesn't feel creative or whatever. There were no excuses. We took care of the palette as we felt like it."

Quake 2 flooded players' screens with a multitude of colors. The result of a broadened color palette translated to environments that varied, but within the context of the story being told and larger setting of the Strogg's home planet. Mines and dungeons incorporated grays, blacks, and browns. Other areas hosted unique architecture such as ziggurats, roads, and computer labs. Blazing, sunset-like color schemes made for distinct backdrops.

"Near the end of Quake 2, one of the projects we had was to go back into every one of our maps and think in terms of colored lightning," said Jennell Jaquays. "That was our first foray into 3D accelerators. We changed lighting, but we couldn't change geometry because it still had to work in software rendering. So, we knew that he had been working on something, and his shiny object was 3D [accelerated graphics]."

Drawing from a deeper spectrum meant that designers and artists had to think about factors such as color theory. For instance, if players spent a lengthy period of time roaming around terrain that was blue, a transition to red backgrounds such as bridges suspended over boiling lava would be much more conspicuous than speeding through structures painted in shades of brown.

The first Quake had boasted unique yet disjointed levels. Quake 2, while still a shooting gallery at heart, presented a consistent world thanks to the combined efforts of id's artists and designers.

"In the early days, we didn't have the bandwidth to think about color," McGee said. "As we became more confident as storytellers, and learned architecture and how to work with tools, and as we had artists coming on board who were able to think that way, the team started to adopt that more and more."

Seamlessness

Quake 2's enemies were conceptualized by senior developers such as Adrian Carmack, Kevin Cloud, and Paul Steed. Outside of initial mockups, bringing them to life was a responsibility shouldered by developers from every discipline within id.

First, artists envisioned characters and added features that communicated their role in the Strogg race. Cloud imagined the Strogg as a cruel race that enslaved and vivisected their enemies to construct abominations of cybernetics and living organisms. Fliers, for instance, are hawk-sized monsters built from cybernetic parts and a human face stretched over their bodies. Berserkers are captured marines implanted with metal arms that pound and pierce. The Gunner is a nightmarish construct of a marine merged with a cyborg body—one arm replaced with a machine gun, the other with a grenade launcher, a spine fused to their fleshy backs.

Assorted weapons from Quake 2.

Once a character's design was more or less pinned down, programmers wired it with a personality. Guards toting laser pistols or machine guns occasionally drop into a crouch to let rockets and bullets sail over their heads. Berserkers sprint at players along a weaving path, making them harder to hit. Such characteristics are minor, but occur frequently enough to establish the Strogg are smarter than the average Imp.

Ambulatory and mean-spirited thanks to a programmer's code, a Strogg became one more tool at the disposal of level designers American McGee, Tim Willits, Jennell Jaquays, Christian Antkow, and Brandon James. Unlike id's previous games, Quake 2 would not divide its levels into episodes. Stratification had worked in previous titles because their simple stories did not hinge on players knocking off episodes in a particular order. Levels are grouped in 10 units, or settings, such as a military base, a prison, a factory, and mines. A unit's levels connect seamlessly by way of doors, access tunnels, corridors, and vehicles such as trams. As players leave one area, they trigger a brief loading screen and then continue playing in the next zone.

Along with visual cohesion from area to area, Quake 2's units charged players with missions broken into smaller tasks. The level designers had to keep those tasks in mind as they worked. "For most of the groupings of levels, we were given an objective that we had to have the player complete in that level," Jaquays remembered. "Usually the theme was, 'Find the big expensive piece of Strogg hardware and blow it up.'"

Before beginning a map, designers were told what objectives players would need to accomplish as well as enemies and weapons should be introduced. Jaquays was assigned the Flyer enemy, which debuts in Unit 1's city-like environs. She unveiled the flyer by having it wait to appear until players reached a point where they had returned to a previously explored area, one of any level designer's best tricks.

"A lot of times we could trigger new events," Jaquays said. "If you went through a map and completed the one beyond it, we could set a flag that said, 'When players come back, there are new challenges.' Guards had shown up, there was a bigger monster that hadn't been there before."

Triggering events and rolling out new challenges can be a clever trick if it's used fairly and logically. Players might feel cheated if they traverse a corridor half a dozen times only to get jumped by a mob of Strogg with no warning. In Quake 2, event triggers tie into progression. Players make two trips to Unit 1's Installation area: first to gain access to the Comm Center, and again to throw a lever that lowers a bridge that leads to Unit 2. Between visits, events such as explosions and the appearance of Jaquays' Flyers are telegraphed in different ways. Flyers, dispatched by Strogg lieutenants to slow the player's momentum, can be heard before they're seen thanks to a telltale whirring sound.

Backtracking to and from areas is one of Quake 2's most distinctive features. Mission objectives send players back and forth, opening up chunks of one region they were unable to enter until completing goals in another, and instilling a strong sense of place. Knowing that players would traverse regions more than once meant the designers would have to map out each area with continuity in mind, treating them like patches on a quilt instead of separate pieces of cloth.

Artifacts, awards, and other memorabilia from id's office in Dallas.

"You make maps that wrap back on themselves so that you pass the door you're going to come out of on your way back, as you're making your way in," explained McGee. "It might be a door, a cliff overlooking [terrain] so that you jump down from the place you've been. The fun in backtracking is when you surprise the player with the way they get back to the point where they started."

Architecture and seemingly innocuous visual cues could be used to foreshadow where a player needs to go or what they should try next. Quake 2's interconnected world meant that players often ended up at a vantage point overlooking buildings and landscapes, teasing where they may be headed next.

"A lot of times you communicate by foreshadowing: 'Oh, there's a key I can see at the other end of the level, so I know what my goal is,'" McGee went on. "But what you don't realize is there's also something right in front of you that acts as the mechanism for allowing you to come back to where you've started. I think that surprise is what makes people feel like, 'That's really cool: This was in front of me all along, and I've walked through it and I'm back where I've started."

Players did not wind up in expansive outdoor areas just to catch a glimpse of the next landmark on their journey. Improvements to id Tech 2 freed designers from the constraint of claustrophobic levels necessitated by the engine's inability to render larger areas. Sites such as massive courtyards and squares broadened Quake 2's scope.

Not that rendering sprawling cities was simple. For all its enhancements, Quake 2 found itself straddling a dividing line. Many players had slotted GPUs into their PCs, but they were a minority. "For Quake 2 especially, the bigger focus was, how do we keep things simple enough that they can be shown in the software renderer?" Jaquays said.

Even with changes such as Potentially Visible Set, Quake 2 had to accommodate players with video cards as well as those without. Larger spaces such as the mountainous Outlands in Unit 8 and the Toxic Waste Dump rotting away in Unit 6 were possible, but had to be crafted with awareness of how much scenery the engine could draw.

"If you saw really large spaces, you knew that designer was overcoming a challenge," Jaquays continued. "I put some really large spaces in, but the thing was to design to make it work, and create a bug-free space that looks interesting. Because of the Strogg architecture, the game had some interesting play spaces in it."

Progress

At first blush, Quake 2's mission-based objectives appear to be smoke and mirrors.

Instead of finding the blue key to open the blue door, players have to lop off a Tank Commander's head and carry it to a door scanner to access a new region. Instead of every creature being a hostile NPC, players penetrate a Strogg prison to find walls painted in gore and their fellow marines crawling and stumbling about, driven mad by torture and vivisection. Ambient noises such as marine chatter over radios flow beneath the heavy-metal soundtrack performed by Sonic Mayhem.

"TRESPASSAH!" A Tank rolls forward, targeting the player.

Greater scrutiny exposes those mechanics as roses by other names. The severed head players use to open a door is really just a keycard. Tortured marines are set decoration, incapable of fighting alongside players or chatting with them. The player's radio regurgitates chatter until players advance to the next objective.

For all the thought and attention that went into settings such as mineshafts and warehouses and Strogg laboratories, Quake 2 is still a shooting gallery. Unlike its predecessor, though, that gallery is active rather than passive.

Quake 2's campaign straddles the generational line between the shoot-don't-think formula created by id, and more narrative-driven FPS games that followed. Most of Quake 2's objectives amount to shooting enemies and destroying objects, but triggering a Rube Goldberg-like alteration in architecture such as a satellite dish beaming a signal into the sky or smashing the Big Gun to bits so that more marines can storm the planet and push the Strogg back remind players that they are agents of change as well as mass destruction.

"I think it was the next logical step," Jaquays said. "I think that was around the time Half-Life was being developed off the original Quake engine, and I know they brought it down for us to see. Shooting things was the Quake method [of progression]. A lot of it was just figuring out where players go next, and [asking] what other things can they do while they're here? What else would be interesting to investigate while they're here? You fight the monster, and you turn the corner, and there's your big reveal of this giant temple in the city, and, 'Oh my god, what's that thing? I've never seen anything like that.'"

Most importantly, hallways tie together rooms that make up area that connect to Units that form a larger setting, deepening immersion and reminding players that they inhabit a world, albeit one where advancement hinges on itchy trigger fingers.

"I think that was an element that arrived as we saw other games doing the same thing, and with the inclusion of new blood like Paul Steed," McGee agreed. "I think that inspired everyone to up their game and wrap more story into what was being presented."

Quake 2's motivation was straightforward, but that was fine. Keeping things simple allowed players to jump feet-first into a Quake sequel without fretting over what happened in the first game. Once players were in, game design, artwork, and sound would do the rest, provided the developers were given time and space to nurture the elements in their care.

Artifacts, awards, and other memorabilia from id's office in Dallas.

"We were going to fight these aliens, the Strogg; they did horrible things to the soldiers and turned them into themselves. That was the storyline," Jaquays summarized. "At the end, we needed a big bad to shoot, and, oh, we don't have time to do it really well, so we'll put this guy [the Makron] out there. That was also classic id: We got rushed at the end."

Relationships

One August weekend in 1997, Jennell Jaquays emerged from her programming cave soaked in sweat and hustled into the common area. Once a week the team met for a show-and-tell, going over what they were working on. She showed one of her works in progress, a secret level found in Unit 1 where players battle enemies in an industrial building and find the super shotgun. Tim Willits, steadily advancing his way up id's pecking order, was the game's de facto lead level designer, looking over the maps built by the others designers and giving feedback.

After the session ended, Jaquays went back to her desk and opened her top drawer. She withdrew a bottle of Pepto-Bismol, unscrewed the cap, chugged a mouthful, replaced the cap, dropped the bottle back in its cubby, and got back to work.

The staff not-so-fondly referred to id's office building as the Rubik's Cube from Hell. Their home away from home was the sixth floor of Town East Tower. All dark windows and steel, the cube-like building squatted just off I-635. A blacktop-paved parking lot surrounded it like a squared moat. All that blackness gave the tower a sleek, futuristic look. It also came with a nasty side effect.

"We had light shining in, and the outside was black, so it got hot in those offices," Jaquays said. "You could pull the blinds, but it still got warm. So, Friday afternoon, hot office, crammed into a 10-by-10 space with a bunch of other guys, watching over somebody's shoulder while they played."

Hailing from a background designing pen-and-paper games, Jaquays needed time to get her videogame-design legs under her. She erred on the side of caution and followed examples set by others. Willits, Petersen, and McGee had all been prolific on Quake, so she stuck to their design schemes at first to give herself a foundation to work on, starting with cube-shaped maps and branching out until she had cultivated a design voice.

"At that point, the id engines were additive engines, so everything had to be put together in a certain way to keep visual seams hidden," she said. "We went for a fairly simple style. The other guidance we had was this really large library, for the time, of surface materials that Kevin and Adrian had been making."

Kevin Cloud and Adrian Carmack shared an office for the majority of Adrian's time at id. Their relationship became symbiotic, each functioning like one arm of a body devoted to turning out iconic artwork. "Neither one of us really took ownership of the art," Adrian said. "We could take [one another's] art and do your own thing with it, and we were totally fine with that. We talked often. Since we were working in the same office, we were always seeing what the other guy was doing. That helps to keep everything cohesive. We knew what we had to do. We had a good relationship."

As id's political atmosphere deepened, some developers looked at them askance. American McGee came to think of them as the secret leadership cabal of id, often holding differing opinions from Carmack, the third of id's three remaining co-founders.

"When you walked past the art department, which was Kevin and Adrian sitting in a room, the door was closed," said McGee. "They lived in an isolation space, and you felt kind of weird going in there because you couldn't talk to one without talking to the other. I worked in the same building with them for four years, but my interactions with them were fairly limited to, 'I need a texture' and 'Okay, you can have that texture,' or 'No, you can't have that texture."

To McGee, Kevin and Adrian operating like wizards behind a curtain was symbolic of how id had changed since he starting at the studio. Like Romero, he had enjoyed id's nonstop crunching on Doom 2 because the context and circumstances had been wildly different than Quake's. Doom 2 had involved coding and design marathons, but it had been fun.

"The innocence was gone," McGee said. "To me, that was the radical shift. Going from a place where when I joined up, it was a bunch of boys having fun with their toys and just having a great time showing the world what they could do with technology, to an internal competition that I think was detrimental to the spirit that led to our games being as much fun as they were. I think those things are intrinsically connected. You can't make a happy, fun product if you have a team that's dysfunctional and unhappy."

According to multiple sources, several tributaries poisoned the well at id. One was ongoing frustration with John Carmack's tendency to make unilateral decisions. Adrian Carmack had weathered storms such as John locking down player-character textures in Quake, but felt worse for artists and level designers, who scrambled to salvage levels and artwork when a game's underlying tech went through abrupt shifts.

Programmers were just as likely to lose progress thanks to Carmack's whims. According to Adrian, John Cash had written numerous advanced AI routines for Quake 2. With them, the Strogg would have been capable of doing more than occasionally ducking to avoid the player's fire. Late in development, however, John Carmack rewrote sections of code that trashed Cash's AI. The game was due to ship soon, leaving Cash with no time to reinstitute his designs.

"At the end of Quake 2, that was just bullshit," Adrian said. "That wasn't the time to do that. You don't do that at the end of a project. He claimed it was the right thing to do. Well, I had a hard time believing that. It definitely wasn't the right thing to do within the last six months. It tanked the AI and a lot of the gameplay elements that we had. There was so much [content] that was cut out. Kevin was pissed, and I don't blame him. Everybody was mad... except for John Carmack."

A Strogg soldier on patrol.

Paul Steed created other problems. Perhaps fueled by his alpha male personality that originated from or was stoked by his years serving in the U.S. Armed Forces, Steed took id's work-first culture to extremes.

"I do recall having some pretty violent interactions with Paul Steed," McGee said. "I would go in and work for 15 or 16 hours and go home, and he would call me from the office at four in the morning and go, 'Where the fuck are you? You should be in the office with the rest of us.' I would tell him, 'I was already on for 16 hours. I needed to go home.' I was just at this limit [of] how long you could stay functional and alive."

While Steed embraced and enforced id's around-the-clock schedule, he by no means set it. John Carmack famously pulled 12-hour shifts from afternoon until early the following morning. There was an expectation—sometimes tacit, sometimes explicit—that others, especially those he favored, work his schedule.

There's a simple logic to developers sharing a schedule. Games are multi-faceted constructs that depend on numerous disciplines to take shape. A level designer in need of a texture must speak to an artist for that texture to be made. Programmers need to consult one another when code they're working on shares resources with code under a coworker's jurisdiction.

Still, some of Quake 2's developers shunned Carmack's all-nighters. Jennell Jaquays had a wife and kids. She set a schedule of approximately eight o'clock in the morning until six in the evening. Weekends were optional, unless one observed the unspoken rule that every day was a workday. As development wore on, extra hours encroached on family time.

"It was difficult, and it cost me a marriage," Jaquays said. "We were at the office a lot, so you ended up not seeing your kids, not seeing your spouse, not being able to participate in a lot of [family activities], or feeling guilty if you left the office to go participate."

Paul Steed seemed to welcome conflict over id's schedule, or any other topic. After Quake 2's release, he created a skimpy female skin—or character—for the game dubbed "Crackwhore" in response to a contest put on by the Crackwhore Clan, a group of female Quake players. When gaming press outlets caught wind of the model, some accused Steed of sexism. Crackwhore may be a clan of female gamers, but the model had been created by a man, which made it sexist.

"I like voluptuous women, and I think guys (and some women) like and appreciate the 'cheesecake' aspect of it. It was just for fun," Steed said in an interview with gaming blog loonygames. "It irks me how people responded to it as far as the sexist and misongynistic [sic] overtones were attached. I'm not a sexist and I'm not a misogynist. Funny thing about it is that more guys than women really voiced their offense to me. How can you be offended by it? It's just a computer image. There's nothing lewd about it. Well...borderline lewd, but nothing pornographic unless you slap some naked skin on it."

When the interviewer pointed out that the Crackwhore character collapsed and wiggled her butt in the air after dying, Steed shrugged off the insinuation. "Well yeah, that was intentional," he said in the interview. "She was 'in character'. I'll make the 'wholsome [sic] girl' model next month and make her fit somehow in a world of death and gibs."

Steed's continued his self-professed infatuation with beautiful women when, after joining WildTangent in 2001, he created a visualizer for music app Winamp that depicted a scantily clad woman dancing to the user's tunes.

In 1999, Steed partnered with Ritual Entertainment's Murphy Michaels to hold a fan contest called Low Poly Lovedoll challenge. The challenge started as an informal contest between artists in the industry over who could build the best low-polygon-count model of a female character before Steed and Michaels extended it to the Quake community at large. The winner would see his or her model rigged into Quake 3 as a custom character, with Steed passing verdict on entries based on the categories of pose, proportions, texture potential, animation potential, and overall use of triangles.

Quake 2 handled outdoor areas much more capably than its predecessor.

While participants were impressed and delighted by the fact that a developer at one of the world's most popular game studios was interacting with them, many looked back on the contest with a critical eye. "The result was essentially a pornography competition, with some models even having incredibly detailed and animating genitalia," wrote Kotaku user Hawk, who competed. "The competition was scrapped because they couldn't find a way to judge the models without them fall into the public's hands and possibly ripped. I think it was for the best, as it was sort of a shameful competition anyway."

In a 2008 episode of The Jace Hall Show, an online program starring the eponymous game designer and founder of Blood and Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor creator Monolith Productions, Hall interviewed Steed about the negative press attracted by the Crackwhore model. "So, they thought you were maybe misogynistic?" Hall asked. "No, no, no," Steed said, "I'm not misogynistic. I just objectify women."

Although Hall's show was known for taking a sarcastic slant on interviews, other comments Hall and Steed made on the episode seemed indicative of his reputation in the industry. "You've been known to go to bars at game developers' conferences," Hall said, "have a bit to drink, and then kick someone's ass if they're talking too much shit to you." Steed hesitated, seeming to decide whether or not to answer. "The games industry people are… they're kind of soft," Hall continued. "They're not trying to hit each other."

"Well, I let them hit me first," Steed replied.

Steed died suddenly in 2012. A prolific designer and artist, his body of work and talent left a mark on every product he touched and inspired peers who set up a college fund to help support his wife and two children. Others, however, found it difficult to shed a single tear.

"Nobody missed him," one developer told me. "This wasn't even during Quake 2. This was his whole life, basically. Beating people up, just being a big bully."

Cohesion

In October 1997, id Software pushed out Q2test1, a demo that let the general public try Quake 2's single-player campaign. "It's always hard to release a version of a product that you know isn’t in its final form," Carmack wrote in a .plan. "There are plenty of things that are getting better every single day, but we need to chop it off at some point to let everyone test it out."

Mentioning that another demo would follow Quake 2's retail release in December, Carmack gave his thoughts on the game's quality so far. "I am pretty happy with the test. I think Quake 2 is definately [sic] the most cohesive game we have ever done."

Quake 2 arrived in stores in early December of 1997, just 18 months after Quake's release and after development had begun in earnest that March. Carmack's assessment bore out. From a fun multiplayer mode and tools that encouraged amateur designers to release modifications, to gorgeous, hardware-enhanced visuals and a single-player campaign that, while as guileless as ever, featured a world teeming with creatures, artifacts, weapons, and mission objectives that gelled seamlessly compared to the first game's hodgepodge of ideas, Quake 2 received above-average marks and took home Computer Gaming World magazine's Action Game of the Year award.

"I thought it was a fun game, that it was cool, and would be well-received. I felt proud of it," said Adrian Carmack.

In response to players and critics who pointed out that Quake 2's more narrative-oriented progression still boiled down to finding keys and shooting everything that moved, John Carmack reminded consumers and his peers alike that the game still accomplished what he wanted it to do.

"We are trying to evolve a genre, not move to a different one," he wrote in a .plan. "If you don’t want a game that mostly consists of running around and killing things, you will be disappointed. We are trying to be cohesive, but not deep. I have high hopes for the games that are attempting to apply our technology to other genres, but don’t look for it in Quake 2."

"We probably produced the game that we could have produced," Jaquays said. "That's the best way to put it. Within the scope of time and personnel we had available, we produced the game that was possible [for us to make]."

Mismatch

American McGee stepped into the art room and froze. John Carmack sat at a table beside Adrian Carmack and Kevin Cloud. The three co-owners wasted no time on platitudes.

"They said simply, 'We're letting you go,'" McGee remembered. "I said, 'Why?' They said, 'We just don't think you fit with the team anymore.' That was it. They didn't give me any more explanation than that. Being fired from id was simultaneously the best and worst day of my life."

McGee walked in a daze, packing up his desk and heading home for the last time. Driving his usual route, he reflected on the last few months, wondering if his termination shared anything in common with an equally surprising departure months earlier.

Veteran developer Sandy Petersen had tendered his resignation midway through Quake 2's development. Jaquays remembered feeling shocked and a little betrayed. "When Sandy Petersen hired me at id, it was on the premise that I was being hired as a level designer to replace John Romero, what John Romero had contributed to the company as a level designer," she recalled. "What I found five years later, when I left id and went to Ensemble Studios where Sandy was working, was that Sandy had hired me to replace him. He knew he was out the door [when he hired me]."

The cohesion of Quake 2's elements ended up in stark contrast to the chaos eating away at id behind closed doors. While Petersen declined to comment on the reason for his departure, he spoke of the toxicity he perceived at the studio. Purportedly, one source of that toxicity was Tim Willits.

"It went from a whole bunch of guys working really hard to make the best games we could, to feeling more like a bunch of jackals eating a carcass," Petersen said. "If you've ever seen, like a National Geographic image of that, the carcass still gets eaten pretty fast, so it's an efficient process, but it's not very pleasant to watch. All the jackals are snapping and snarling at each other. That's kind of where [our culture] went, from us all being a team to looking over our shoulders. It was a great team, and even the toxic version [of the team] was able to make good games."

Thanks to 3D accelerators, Quake 2's water was transparent, letting players inspect pools before diving into them.

American McGee was no stranger to Tim Willits' alleged behavior. One morning a year or so earlier, McGee had stepped into the Town East Tower's elevator. Willits entered with him. Before long, Willits turned to him, grinning.

"He turns to me and he goes, 'Hey, did you ever have butt sex with your ex-girlfriend?' We all knew each other; he knew my ex-girlfriend," McGee recalled. "I remember saying something like, 'Tim, fuck off,' or 'I don't know what you're talking about.' And he looks at me and he goes, 'Well, I had it last night, and it was great.' And that was it, and he walked away."

McGee did his best to ignore Willits. Around the office, he'd become infamous for needling anyone he considered equal to or below his station. His goal, McGee speculated, was to get them so riled up they could not concentrate on their work. One morning McGee had found a series of Post-It notes stuck to his door. Each contained crude language. McGee assumed Willits was the perpetrator, but no one said anything, so he didn't speak up either.

"I think he was just trying to push everyone out of the way," McGee said. "Ultimately what he wanted was to be the main guy in control. He was incredibly ambitious and cared not for how he moved up, only that he moved up."

"He was definitely a politician," Adrian said. "As he liked to say, 'Never turn your back on a level designer.' Both he and American were politicians, but Tim could be brutal. If Tim had it out for you, it wasn't good for you."

According to Petersen, Willits had his eye on id's upper echelon of management from the moment he became a full-time hire. After Romero was fired, Willits had coveted McGee's status as John Carmack's golden boy. According to this developer, Willits set his sights on eliminating McGee. Their feud reached a boiling point when McGee ran into trouble designing levels for Quake 2.

"American could tell something [was not right]," Petersen said. "So he went to Carmack and said, 'What should I do?' John Carmack said, 'Okay, to make your levels look better, go and talk to Tim.' And Tim Willits could make absolutely spectacular-looking levels. They were great levels. He said, 'Talk to Tim. Look to him to show you how to make your levels look really nice.'"

Willits deployed misdirection to further attenuate McGee's status with management. When McGee submitted new and revised levels for appraisal, Carmack lost his temper and accused him of doing A when he had expressly wanted B.

"American was horrified," Petersen said. "He said, 'Yes, I did just what he said.' Basically, what had happened was Tim Willits had literally told American the opposite of what he should do, to get him in trouble with John Carmack. And Carmack couldn't believe it. Who could be that dirty? He absolutely refused to believe that Willits had done it, but he had. That was Tim Willits literally tanking American McGee."

McGee remembers the situation differently. Carmack had no say in level design, and would not have given him or any other designer an evaluation. Any feedback would have come from Adrian Carmack, Kevin Cloud, or the studio's de facto lead level designer. "That's not to say he didn't. I just don't recall it," McGee said. "Somebody, Tim or someone else, would come to me and say, 'This isn't really the direction we want you to go. Why don't you try something different?' I think at that point, they had unofficially elevated him to lead level designer. He had purview over that process, sort of the instruction-and-review process. I remember he had been elevated to a position above mine, for sure."

Whether Carmack reviewed McGee's levels or not, he may well have had trouble believing Willits would sabotage a coworker. A troublemaker and brownnoser, he was also considered the best level designer on staff.

"I will say that I'm not a huge fan of Tim Willits, but Tim Willits got Quake 2 done," Jaquays said. "He built a lot of the content that ended up in Quake 2. The lion's share of content is stuff that he developed."

American McGee not only recognized Willits' ability. He confessed to his own failings. "I feel certain he was a large part of the reason I got fired," said McGee. "But in saying that, I also want to be very clear that I also had my own issues and weaknesses. I don't think he could be called the primary cause [of my termination], but I definitely think he was high on the list."

"The owners didn't know at the time, but we found out later about Tim, and how he told American to do the opposite," confirmed Adrian Carmack. "Yeah, he did that, but that wasn't what got American fired. The writing was already on the wall: American was either going to leave of his own accord, or [be fired]. That one incident wasn't the final nail in the coffin."

McGee could feel his interest in the job slipping. His run-ins with the likes of Tim Willits and Paul Steed, coupled with the long hours, had taken their toll. Money didn't help matters. Far from being broke, McGee was 23 years old and flush with cash. Like many of his peers, he spent extravagantly, buying cars, clothes, a house, and eating out almost every meal. The parties were his true weakness. After working 100-hour weeks, he cut loose with friends, a habit that put his work performance in jeopardy.

"Hooking up with the Nine Inch Nails guys led to a level of partying I wasn't accustomed to," McGee said. "I know there were more than a few weekends when I was able to rest, but instead I would party so that when I would go into work on Monday, I wouldn't be 100 percent. I think that sort of thing definitely started to become noticeable to others."

Peers did notice. "Brandon James and I, and even John Cash, had to go in, fix, and in some places, complete American's levels in Quake 2 in the final days before we went gold," said Jaquays. She and the others had to review McGee's levels and add bits and pieces he had forgotten, such as starting locations for multiple players.

"I think there were times when everyone there might have been able to look at me and say, 'You're having a bit too much fun outside of the company,'" McGee admitted. "Sometimes I was hanging out with them more than was necessarily required to get music and sound effects done. But, again, I was a 23-year-old kid being told I can hang out with rock stars and smoke cigarettes with David Bowie. It was like, I like my job and all, but if you don't mind I'd like to go over here and have a little fun. I guess that wasn't the proper response."

As McGee's problems mounted, his relationship with John Carmack soured. While McGee's behavior was grounds for their friendship to erode, id's tech guru had a reputation for distancing himself from those whom he believed had fallen out of sync with his goals. "My fiancé at the time didn't like us living next door to John Carmack, because Carmack would come over unannounced quite often and want to bounce ideas off of me. She really wanted us to leave that house," said McGee.

McGee and his fiancé sold their house next to Carmack and moved a few miles away. That proximity gave them more privacy, but it also removed McGee from a person who, he realized in retrospect, had been a stabilizing force. "It put me in a situation where I didn't have a big brother-type living next door to keep me under control for fear he might pop over at any time. I definitely think there was a sort of downward spiral."

Female Strogg warriors.

After finishing Quake 2, McGee and many other developers took extended leaves to catch up on rest and piece together their personal lives. When McGee returned, Adrian Carmack and Kevin Cloud assigned him tasks he found bewildering. "I remember the artists being very weird toward me," remembered McGee. "Adrian and Kevin started tasking me to produce geometry. They would say, 'Come up with a new design idea for a door, and the arch surrounding the door.' I couldn't quite get my head around what they were asking me to do in terms of what was going to satisfy their requests."

In early March of 1998, McGee was fired by Adrian Carmack, Kevin Cloud, and John Carmack. Years of frustration and fatigue boiled over. "I remember breaking down right there in the room," McGee said. "Just saying, 'What? Why?' And they just kept repeating 'It's not a match' or 'It's not working out.' They wouldn't give me any more concrete information than that."

By the time McGee pulled into his driveway, he felt more at peace. For all his mistakes, working 16 to 18 hours a day, six or seven days a week, had been untenable. After finishing Quake 2, he had contemplated approaching management with a request that the studio as a whole ease off the gas. Recuperating for a few weeks or months was futile if it meant the developers were resting just to slip back into crunching.

Perhaps being fired would turn out to be a blessing. The time had come for McGee to stretch his wings and try something new.

"I thought, What's going on? Why am I feeling like this? Why do I feel relieved? I inspected it, and ultimately realized I was glad to get out of there. I was glad to get away from it," McGee said. "I feel bad about the way it ended and the loss of friendship with John. I think I mishandled some things there. I was quite young."

Enjoying Rocket Jump? Click here to share your thoughts with other Shackers in the Chatty.