Freedom

James Ohlen stood at the foot of one of the Caves of Chaos. Tentatively, he took a step inside. The mouth yawned open. Blackness swallowed the light filtering through a canopy of fronds overhead.

Swallowing, Ohlen stole a glance at his friend. He sat hidden behind a screen of paper. Waiting for Ohlen to make a move. And he was smiling.

A noise from inside the cave. Ohlen jumped. It had been a grunt. It sounded like a grunt. Low and animalistic. Then another sound echoed out, slow and heavy, like footsteps dragging over dirt and stones. Ohlen wanted to run—but he also wanted a closer look. He stayed put. His friend’s smile broadened into a shit-eating grin.

He watched as a shadowy form took shape. It was growing larger, coming closer. He squinted, took in sickly yellow skin, a broad, squashed nose, large, bat-like ears, and red eyes that glowed dully. Stupidly. A goblin.

Ohlen’s palms broke out in a sweat. Goblins stood three-and-a-half feet in stature, but to Ohlen it may as well have been a giant. He raised his sword and braced his feet. The beast saw him, yelled in triumph, and charged. Ohlen raced forward to meet it.

Steel flashed. The goblin’s roar of triumph heightened into a screech. Hot blood splattered Ohlen’s shirt, but he failed to notice. The goblin dropped to the ground at his feet, dead.

Ohlen’s eyes widened until they were as large and bulbous as the goblin’s. Then he threw down his sword and dashed out of the cave and up the stairs of his friend’s basement.

"My first kill was a goblin,” he said. “I thought, at ten years old, that this was the most amazing thing. I had to run up and tell everybody how I killed the goblin.”

In that moment, Dungeons & Dragons sunk its hooks into Ohlen. He was happy to be snagged. The freedom of the game, a joint creation by fellow nerds Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, enthralled him. His buddy from school had been running Gygax’s Keep on the Borderlands campaign, an introductory adventure aimed at beginners. The plot sees a party of swashbucklers make camp at the Keep and then venture into the surrounding wilderness to clear out the monsters making trouble in the Caves of Chaos.

What Ohlen loved about the campaign was that its plot was just a suggestion. As long as the story was being told by a flexible dungeon master, the players—Ohlen and his buddy’s ten-year-old sister—could go anywhere, do anything.

Ohlen’s school chum ran his campaign for a year before the family moved away. A void opened in Ohlen’s life. He missed his friend, but what he really needed was someone to whisk him away on more sword-and-sorcery escapades. He asked around school to find out if anyone ran stories. Ohlen got strange looks in rely. It wasn’t that his friends thought he was a nerd. They’d just never heard of the game and needed someone to show them the ropes.

Ohlen anointed himself dungeon master and invited all comers to enter his domain. "I even advertised at local stores and public libraries to get games going. I was the typical, basement-dwelling troll who was always nose-deep in fantasy books."

All kinds of kids answered his call for players, from “basement-dwelling” trolls like him to the quarterback of the high school football team. Over the next several years, Ohlen’s hometown of Grand Prairie, Alberta, Canada, became his staging ground. He deftly juggled three campaigns at once. "It became my addiction," he said.

Ohlen’s enthusiasm for tabletop gaming led naturally to a job running a comic book store in Grand Prairie. To casual shoppers, he was James Ohlen, proprietor of superhero monthlies. To his players, he was the ultimate storyteller. He had pared the campaigns he was running down from three to two. Each was so popular he had to draw up waiting lists for players.

For a while, life proceeded at an easy clip. Fresh out of high school, Ohlen sold comics by day and held sway over card tables by night. Then, in January 1993, Superman died.

Cover Stories

The event was unprecedented. In a story arc so gigantic it spilled across all of publisher DC’s Superman books, the Man of Steel died when he and his nemesis, the alien Doomsday, traded fatal blows.

Countless stories had featured the popular icon narrowly escaping the likes of Lex Luthor, Brainiac, and the glowing green rock kryptonite from his home planet of Krypton. But dead? Superman? Never.

Yes, DC insisted. Dead.

Mainstream media pounced on the story. Outlets from NPR and Newsweek to People magazine and the Washington Post covered the fictional death. Newsday made it a cover story. Saturday Night Live dressed actors as heroes to attend his funeral.

Unfortunately, Superman’s death proved contagious. "In the comic book industry, there was a glut of alternate covers,” Ohlen said. “Essentially, the industry started focusing on collectability instead of actual storytelling.”

Superman issue #75, the book where the eponymous hero and Doomsday killed one another in dramatic fashion, was printed with three covers. Two were aimed at collectors. The third could be found at most newsstands and bookstores. Canvassing retail outlets with multiple covers was the latest in a string of failed marketing stunts by DC. When sales of the Superman monthly comic dropped, the publisher heightened the romance between reporters Lois Lane and Clark Kent that culminated in their engagement.

When Warner Bros. developed Lois & Clark, a TV serial that would focus more on the title characters and less on cape-and-spandex antics to draw in an older audience, DC executives dreamed of huge numbers by having the comic and TV incarnations of the characters wed around the same time. To delay, they killed Superman.

What they didn’t tell readers was they had every intention of bringing him back.

At first, the stunt worked. DC sold millions of copies of Superman #75 to stores. Readers bought it in droves. Other publishers followed the money. Marvel’s X-Men #1, co-helmed by famed comic writer Chris Claremont and featuring the debut of soon-to-be-legendary penciller Jim Lee, shipped with seven alternate covers. Tod McFarlane’s Spider-Man hopped on the bandwagon. In 1993, DC kicked off Knightfall, a Batman crossover in which the Caped Crusader’s spine was broken by villainous newcomer Bane in Batman issue #497—available in multiple covers. Three issue later, DC celebrated Batman #500 by rolling out a high-tech Bat-suit for Bruce Wayne’s replacement. Cover count: two. One regular, one collectible.

Readers snatched up any issue with alternate covers, believing the books were destined to be worth big bucks. A few years later, the jig was up. Superman returned from the dead. Bruce Wayne was soon ambulatory and back to cleaning up Gotham City’s mean streets. For readers and sellers like Ohlen, the truth sank in. If a superhero had been killed or crippled only to return to action, the super-duper collectible issues in which they had been brought low were worthless. Readers caught on, too.

"What happened was, all the collectors, the people buying comics not for the stories but for collecting, got out of the industry in a very short period of time, but all the stores were still ordering massive amounts of comics,” remembered Ohlen. “Suddenly you were stuck with this huge stockpile of comics that no one was buying."

Ohlen was left holding a bill for unsold books. One afternoon when he was twenty years old, Ohlen picked up the phone. A supplier greeted him and, in a deadpan voice, told Ohlen he needed to pay up or he’d pay a visit and break his kneecaps. “I was like, ‘That's a very funny joke.’ It was a stressful time, but I learned a lot of lessons from a failed comic book store as well. It's amazing how you learn life lessons when people are threatening to break your kneecaps. Jokingly.”

Magic: The Gathering’s arrival coincided with the comics industry’s slump. The collectible card game casts players in the role of wizards who cast spells and summon creatures using playing cards. Players can buy premade decks, or booster packs that contain a random assortment of cards. Unlike superheroes, Magic cards don’t die. They retain their value because players can add or remove them as they build custom decks.

Wizards of the Coast’s collectible card game swept through specialty stores. Ohlen and other proprietors cleared shelf space for booster packs and other supplies such as gaming dice and plastic sleeves to protect cards. His kneecaps were safe… for the moment.

During lulls, Ohlen headed downstairs to check on a different type of game. One of his buddies, Cameron Stofer, had taken over the store’s basement to program a computer roleplaying game. Other friends including Ben Smedstat, Marcia Tofer, Cassidee Scott, and Dean Anderson popped by to hang out.

One day, Cameron told Ohlen about a friend of a friend, Dr. Ray Muzyka. The doctor had co-founded a small computer-game company called BioWare with two other M.D.s, Greg Zeschuk and Augustine Yip. BioWare’s co-founders loved D&D as much as they enjoyed practicing medicine. All three had graduated from the University of Alberta. All three practiced medicine. And all three dreamed of one day hanging up their stethoscopes to make games full-time.

Muzyka, Zeschuk, and Zip had begun dabbling in software development between classes. Their first gig was writing educational software for the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Medicine. They pooled $100,000 to open BioWare, starting out in Zeschuk’s basement. Licensing Dungeons & Dragons was expensive, so had they thought smaller, writing code and drawing artwork to build a prototype for a mech combat game called Shattered Steel. They hired a few more developers including Scott Greig, their head programmer, who shared their chief goal of creating a computer game set in Dungeons & Dragons’ world. Shattered Steel would bankroll their dream game, or so they hoped.

With a small staff of six developers, the doctors were looking to hire on more developers at the exact moment Ohlen’s store was drowning in red ink despite Magic’s popularity.

Ohlen shuttered his business. Together, he and his group of friends joined the upstart team. "They were just looking for people who would work for peanuts, and wanted to work on a D&D game,” he said. “When the six of us came down, we essentially doubled the company's size. I think we were employees seven through twelve.”

Steel

By the time Ohlen and his friends joined BioWare, Shattered Steel was chugging along. Players piloted a mech, like in Activision’s MechWarrior game published in 1989. However, Shattered Steel was deeper. Tactical combat was the main draw, but the doctors wanted to showcase character development and dialogue.

Ohlen was less keen on mechs and missiles than he was dragons and firebolts. Still, he wanted to impress the doctors. Pulling artwork from old science fiction novels that had been published in Sweden, he put together a bible—a document that outlines a game’s vision—to help define Shattered Steel’s world.

"I was very much upfront in saying, ‘This art isn't mine. I've taken it from another source,’ but I also knew it would appear new to them," he said. "It was kind of sleight of hand: ‘Look at this amazing bible, and all this art you see is completely brand-new because you've never seen it before even though you're giant science-fiction-and-fantasy nerds.’ It made the bible look that much more professional and awesome. It was my many sleights of hand when it comes to design. Design is often about making what you're doing seem a lot greater than what it actually is."

Work quickly became Ohlen’s new obsession. BioWare’s doctors held on to their practices even after BioWare moved into a small office, and were a blast to hang around. Zeschuk cracked jokes and chatted with everybody. Muzyka was more like the ultra-logical Vulcan race from Star Trek according to Ohlen, who framed the comparison as the highest compliment.

"They really bounced off each other in a good way. Together, they formed a very strong leadership core,” he said.

Eventually, the doctors determined that they needed a publisher’s help and deep pockets to finish the project. They shopped the game to ten publishers. Feargus Urquhart, a young and ambitious producer from Interplay Productions, expressed interest.

Urquhart landed the project purely by luck. "The head of QA for Interplay when I got hired in '91 was a guy named Rusty Buchert,” recalled Urquhart. Buchert and Urquhart had both got their foot in the door by testing games at Interplay. Both were promoted to producer roles, and both found themselves running multiple products. When Buchert landed games developed with the Star Trek license, he had to trim projects to give his new roster more attention. One of those was Shattered Steel, then known as Metal Hide. Urquhart stepped up.

The BioWare team wanted cinematics to advance Shattered Steel’s narrative between levels. Urquhart found the perfect artist to the job. "I came in and Rob [Nesler] said, 'You're going to do the cinematics for this new game they're working on, Shattered Steel. We're publishing this company's first game. They're called BioWare,’” recalled former Interplay artist Tim Donley of his first conversation with Nesler, Interplay’s art director.

Donley tried to hide his disappointment. Like most of the team at Interplay, he was a D&D nerd and preferred to be drawing elves and wizards. His opinion changed when Urquhart introduced himself by shaking his hand and then showed him to his desk, where Donley found a giant stack of papers. That, Urquhart said, was Shattered Steel’s script.

Donley had six months to render everything BioWare needed for the game’s movies. He dropped by BioWare, based out of Edmonton, Alberta, and was surprised by what he found. The office was cramped, almost the size of a studio apartment. Fortunately, the small team’s enthusiasm for making games was inversely proportional to the size of their workspace.

He condensed their script and turned out just over a dozen tightly made cinematics. “Their first game was Shattered Steel. Their second was a little bigger than that,” he said.

“Stupid”

Even during the stressful days when he thought he might be in danger of a supplier taking a hammer to his kneecaps, Ohlen never stopped running D&D campaigns. He simply cut back or ramped up as other obligations permitted.

Working at BioWare took up more and more of his time, so he focused on running one campaign for his workmates. As he had during high school, he tailored his balance of storytelling and beating up monsters based on the demands of his players. His workmates were eager, in part because most of the staff wanted to do more than play roleplaying games. Like Ohlen and the doctors, they wanted to make their own. They would soon get their chance.

Shattered Steel launched to tepid reviews in 1996. Many critics stated that the game’s attempts at complexity fell short of other titles in the genre, namely MechWarrior 2. Fortunately, the doctors had diversified. Their team was busy preparing Battleground Infinity, an RPG whose scope was as huge as its title promised.

Battleground Infinity started as a tech demo made to show off programmer Scott Greig’s proprietary tech. Greig called it the Infinity Engine. He was building the Infinity Engine to take advantage of 3D graphics cards, emerging hardware devoted to blasting pixels and polygons onto screens—tasks that had previously been carried out by the user’s processor.

The centerpiece of Greig’s demo was a sprawling background displayed from an oblique angle, like a chess board viewed from one corner so resembles a diamond instead of a square.

"You had a side-scrolling bitmap, and thus, you could have lots of unique art to use for your environments," Ohlen said of Battleground Infinity. "That became the basis for the Infinity Engine. Scott Greig was kind of the father of the IE, and so it was his thing. It even had his art, his programmer's art. I actually have the disk here in my house," he finished with a laugh.

The doctors wanted Battleground Infinity to flourish from awesome tech demo into a massively multiplayer RPG (MMORPG) in the vein of Ultima Online. Hundreds, even thousands of players would occupy the world in real-time to complete quests and learn more about a mythology centered on a pantheon of gods.

Muzyka, Zeschuk, and Yip sent an early version of the demo to Feargus Urquhart at Interplay. Urquhart had risen even higher to the helm of Interplay’s RPG division, Black Isle Studios. "It looked okay,” Urquhart remembered. “It was hard to get my [head] around, so they started pitching other publishers."

Urquhart had trouble grasping Battleground Infinity because he wasn’t sure what BioWare intended it to be. Did they think they could deliver on a game the scale of a proper MMORPG? Because to Urquhart, it was more like a real-time strategy game: top-down, isometric view; numerous characters running amok on a battlefield.

Before long, BioWare had offers from Sir-Tech, the studio that had made the Wizardry series of RPGs popular on the Apple II, and Westwood, creators of Command & Conquer. The doctors held off on signing contracts and went back to Urquhart with an updated demo. He came away impressed. The game’s setting and characters were grounded in fantasy, with players controlling a party of characters.

Just like in a Dungeons & Dragons game.

“Something went off in my head,” Urquhart recalled. “I took this party-based [concept] and called them up and said, ‘What if we made this a D&D game?’ They said, ‘That would be really cool.’”

Urquhart went to his boss at the time and showed him Battleground Infinity. The manager gave him a get-outta-town look. Roleplaying games had been Interplay’s bread and butter at one point, back in the heyday of The Bard’s Tale, which had put Brian Fargo and his company on the map. Now the genre was dead or at least on life support. Compared to cutting-edge genres like first-person shooters and real-time strategy games, RPGs were slow and too complex for mainstream consumers. They were ugly to boot, the polar opposite of fast, gorgeous games like Doom, Myst, and StarCraft, which topped sales charts.

The manager ended his meeting with Urquhart with the ultimate dismissal: Battleground Infinity was stupid.

Urquhart dug his feet in. "It was one of those times when I said, ‘That's not good enough. No. It's not stupid.’"

While Urquhart had pull within his division, Black Isle was ultimately one piece of Interplay. He went up the next rung on the corporate ladder to Trish Wright, his boss’s boss and the vice president of product development and marketing. He told Wright he believed in his gut that BioWare’s game had the potential to be a huge success, and that Interplay would be foolish to pass on it. Wright told him to show her the demo.

Urquhart paused. His computer was old and hadn’t been capable of running the demo in all its glory. He went to Michael Bernstein, one of the company’s programmers, and asked him to load it on his machine. Wright and Urquhart watched over Bernstein’s shoulder. When the demo finished, she turned to Urquhart and asked if Brian Fargo had seen it. Urquhart said he hadn’t.

Wright picked up the phone in Bernstein's office. A few minutes later, Fargo watched the demo play out on Bernstein’s screen while Urquhart gave his elevator pitch: a cutting-edge, party-based RPG based on the D&D license.

At the end of the demonstration, Fargo told Urquhart to sign it.

"There was an old Amiga game, The Fairy Tale Adventure, that was isometric, and it was absolutely gorgeous,” Fargo said. “It did really, really well, even though it was light on gameplay. It wasn't a deep product, but it looked beautiful. What they were doing visually, isometric—every screen looked like a JPEG. It didn't look like a bunch of building blocks. The screen was clearly delineated. It looked like somebody had free-hand-drawn every single screen, which was what they did. I was super impressed by that. That sold me."

Although Fargo’s support had buoyed belief in niche products in the past, Urquhart and Chris Parker, the producer Urquhart assigned to the project, were two of the only developers within Interplay who believed in BioWare’s chances. Interplay’s UK division didn’t even bother forecasting sales. Anything connected to Dungeons & Dragons was doomed to fail.

"Interplay didn't even think they would make their money back,” Parker remembered. “They thought they might sell 100,000 units. When we got really close to launch, after E3 in '98, I think they upped their sales forecast, and they might have expected us to sell 150,000 units. Everything that we did, our publishing and QA efforts, we did without super strong support."

Interplay’s sales and marketing teams were convinced that the company was flushing away money, almost literally. "It was going to be called The Iron Throne,” Ohlen recalled of the game. “Eventually Trent [Osner] made lots of jokes, toilet jokes, so maybe it's better the name changed. The name Baldur’s Gate came from Feargus Urquhart. He was the one who wanted us to use that name, which is, of course, the name of the city where the end of the game takes place."

Back at BioWare, James Ohlen found himself standing at the mouth of another Cave of Chaos. No mere goblin lurked within. This time, the enemy he faced was inexperience. Neither he, nor anyone else at BioWare, had ever built a game from conception to release. Many pieces of Shattered Steel had been in place when Ohlen and his friends had joined BioWare, and much of the heavy lifting had been done by Interplay. The D&D license meant a bigger opportunity. It also meant higher stakes.

On the other hand, the fact that they still didn’t know what they were doing could be viewed in a positive light.

"We didn't know what the rules were. We didn't know what could be done and what couldn't be done. But we did have the Infinity Engine," Ohlen said. "We had Feargus Urquhart, Chris Parker, and Chris Avellone, and a lot of veterans on that side who were able to give us a lot of lessons, advice, and help. That was hugely useful for us. But I think the fact that we hadn't done this meant that we weren't trying to copy. We didn't restrict ourselves. Because we didn't know what was impossible, it allowed us to go in a different direction than what a lot of the rest of the industry was doing."

Fan Service

Just as BioWare’s Dungeons & Dragons-licensed game was getting off the ground, the D&D brand was in danger of going the way of the dodo bird and Superman.

As computer games grew more sophisticated, managers at TSR felt threatened. Their pen-and-paper game was no longer selling at record numbers. They decided to branch out, experimenting with technologies such as CD-ROM. Pushing into hardware and software would cost a mint, so TSR partnered with Random House.

Per the terms of their publishing agreement, Random House would pay TSR when products arrived in their warehouse, ready to be shipped out to stores. Those terms put the onus of production on TSR: They would have to design products, then come up with money to pay printers before seeing a penny from Random House. They had been churning out supplements and settings for Dungeons & Dragons so quickly—cannibalizing their own products—that they had racked up debt with their printer. The printer tightened the noose around TSR’s neck by forcing them to sign an exclusive agreement that prevented them from skipping out on their tabby going to another printer.

Just before Christmas 1996, Random House returned millions of dollars in unsold products. TSR laid off thirty employees, and its printer announced a moratorium on printing until TSR paid up. The game’s publisher, Magic creator Wizards of the Coast, granted a stay of execution by purchasing TSR.

All Dungeons & Dragons materials and licenses became the property of Wizards. whose representatives were all too happy to work with BioWare and Interplay. Their embryonic game seemed poised to do for gamers what author R. A. Salvatore’s novels starring dark elf Drizzt Do’Urden had done for readers years earlier: Introduce a brand-new audience to the magic of Dungeons & Dragons and revitalize the brand.

Working with Wizards of the Coast seemed to be a breeze. Someone at BioWare or Interplay would make a suggestion, and the team at Wizards would just shrug. "Pretty much anything that was in one of the novels was off-limits without prior approval,” said Chris Parker. “Drizzt is actually in Baldur’s Gate, but we had to ask if we could use him. Pretty much everything else was on the table."

Perhaps one of the reasons Wizards didn’t sweat BioWare’s and Interplay’s decisions was because both studios were intent on being respectful to the source material. Scott Greig devoured everything related to D&D and its Forgotten Realms setting, where their game would be set, he could get his hands on. For James Ohlen, getting to make a game set in his favorite universe was a literal dream come true.

"I got to meet Gary Gygax and David Arneson. That was super cool, and I kind of let my inner nerd come through," Ohlen said.

Ohlen and Greig demonstrated their fandom by taking charge of the project. Greig’s main job was to continue building out the Infinity Engine. There was ample room for improvement. His Battleground Infinity demo had consisted almost entirely of the sliding bitmap designed to wow publishers. Over the next two years, he added built-in tools that facilitated content creation for artists and designers. The engine’s conversation editor let designers create branching dialogue so players could choose what to say while conversing with NPCs to suit their character’s personality, and receive appropriate responses.

Other customized systems included an interface to view journals that players found while exploring, another interface to display area maps, a fog of war that shrouded unexplored terrain in darkness and peeled back as players pushed ahead, and nitty-gritty details such as efficient management of memory. Greig took input from Black Isle’s producers, who had suggestions based on their experience developing massive games such as Fallout and Fallout 2. The post-apocalyptic games had been made entirely by hand, without any tools or engines to standardize details such as the dimensions of doors that ended up prolonging development.

"When you went to six different areas in the game, they were made by six different designers with six different kinds of doors,” Parker said of both Fallout titles. “What Feargus and I really pushed for with BioWare was to have them create everything with sets of tools so that sort of situation didn't arise. You had a character editor, an area editor, an item editor, all of these different things, and each of them [generated] very uniform data files. It was harder to make something that was broken in the engine."

Parker watched the Infinity Engine blossom firsthand. The first item on his to-do list when he was assigned to the project in March 1997 was to visit BioWare. Over three days he asked questions of the doctors, of Greig, and of other developers. His goal was not to pry or micromanage, but to understand the team’s vision so Black Isle could help them realize it. BioWare was small, roughly thirty-two people in the beginning of development and approximately fifty by the end late 1998.

Small, but passionate and committed. One thing Parker and Urquhart found amusing was the emphasis BioWare’s doctors put on the Infinity Engine. "They named the engine because they wanted to create another business, which was licensing engines," Urquhart explained.

In the mid-1990s, few developers had the foresight to license their technology. Not even id Software co-founder and engine programming whiz John Carmack thought much of branding until later, when id retroactively christened platforms that had been generated millions.

The doctors’ reasoning was simple. Black Isle, by way of Interplay, was Baldur’s Gate’s publisher. That made Interplay their main financier, and therefore able to claim some ownership of the game. Likewise, the Forgotten Realms setting belonged to Wizards of the Coast. The game’s technology was the one thing they owned. "Ray and Greg were visionaries,” Ohlen said. “They were always several steps ahead of the rest of the studio. It wasn't a secret, but they wanted to make sure the BioWare brand was strong, and the brand of the Infinity Engine was strong."

Urquhart fully grasped how important the engine was to the doctors’ plans for the future when, after firing up a build of Baldur’s Gate, he had to sit through introductory videos that advertised Interplay, Black Isle, BioWare, and the Infinity Engine before the game finally dropped him at the main menu. "I had to call them up and had a very uncomfortable conversation where I said, ‘This game is not meant to be an ad for your engine,’ and they wanted it to be that. That was Ray and Greg's push, and they made sure that any conversation they had about the game was that it was made in the Infinity Engine."

While Greig wrote code, Ohlen leveled-up his dungeon mastering by stepping up as the game’s lead designer. "The advice I give people about careers [in game development], one of the big rules, is when you have opportunities come up, you need to take them," he said. "I was going to design the entire game, do everything. I was taking control. I was working 100-hour weeks, and I knew that, just because I loved it, not because I [was told to]. It just wasn't work for me. I created my job because I wanted to create it at the time."

Ohlen knew he didn’t have total autonomy. Major decisions still had to be vetted by the doctors. But Muzyka, Zeschuk, and Yip were hardly dictators. They acknowledged Ohlen’s passion for the project and gave him carte blanch to design a compelling virtual world.

Of BioWare’s co-founders, Muzyka had the most profound impact on Ohlen. "I never had a father growing up, so Ray was kind of like a father figure to me, even though he's only four years older than I am."

At various stages during Baldur’s Gate, Muzyka gave Ohlen a piece of advice that has guided him on every project he has managed to date: Trust, but verify. "He was very good at trusting people, but at the same time, verifying that they were doing what they said they were doing,” Ohlen said.

Muzyka’s words struck a chord with Ohlen: When applied to game development, they functioned as a natural extension of the in-game agency BioWare wanted to give players. "When you're in a work environment, you want the people working for you to feel like they have the freedom to do what they want. You're going to get the best work from them if they feel autonomous. That was one of the many lessons and values that he instilled in the studio, and in me."

Living and Breathing

Ed Greenwood was stumped. It was 1967, and the ten-year-old had read every book in his father’s library. Bereft of new material, Greenwood did what any bookworm would do. He wrote his own.

Eight years later, Greenwood discovered Dungeons & Dragons. Like Ohlen would be years later, he was even more enchanted by the prospect of running his own campaigns than he was participating in the stories of others. He put together a module based on a setting he had created during his boyhood to contain the characters and places he had dreamed up and written down. He called it the Forgotten Realms.

The Realms had once existed as a parallel setting to earth, until earth’s inhabitants gradually forgot about the magic that dwelled there. When he landed a job as an editor at The Dragon magazine, he penned lengthy articles describing the Realms. In the mid-1980s, TSR went looking for more campaign settings to expand Dungeons & Dragons. Greenwood’s Forgotten Realms seemed a perfect match. Over time, the Forgotten Realms evolved into one of D&D’s most popular settings. Greenwood’s chief avatar, Elminster the wizard, became an iconic figure, as did R. A. Salvatore’s Drizzt Do’Urden.

Until BioWare and Black Isle got hold of it, Baldur’s Gate was just one of many cities in the Realms. Set on the Sword Coast, a coastal region that borders the Sea of Swords, Baldur’s Gate is a wealthy port metropolis where merchants prosper thanks to “the Gate’s” prime position for trade on land and sea.

The developers at BioWare and Black Isle Studios pegged Baldur’s Gate as the perfect setting and title for their game, but it would be one of many locales that players would visit over their journey. "Aesthetics were very much a part of what we wanted to try to accomplish,” Chris Parker confirmed. “If you were to go back and listen to Ray or me talk about the game back then, this was one of the things we thought was very important.”

Every developer at BioWare and Black Isle Studios was familiar with the Gold Box RPGs. A series of D&D-licensed games published by SSI (Strategic Simulations, Inc.) over 1988 through 1992, the series had been embraced by fans, but had fallen to the wayside as trends such as first-person shooters and technologies graphics cards emerged.

“We could make things that were amazing,” Parker continued. “I think that's all we were going for: How do we make a beautiful, high-fantasy world, and try to take advantage of that in as many ways as possible?"

BioWare’s team implemented technical and creative solutions to wow players with fantastic visuals. Baldur’s Gate cycled between day and night. New quests and character interactions unlocked depending on the time of day. To create environments, Greig programmed the Infinity Engine to employ pre-rendering, a process that takes complex backgrounds made up of 3D elements and flatten them into a single image.

More developers were using pre-rendered backgrounds to great success. In 1996, Capcom’s Resident Evil made waves for the atmosphere baked into its haunted mansion. The Polygonal characters were able to move around the game’s pre-rendered corridors and rooms, as if they had stepped inside photographs of the spaces.

Backgrounds rendered in real-time with complex elements such as lighting and three-dimensional space may be too complicated for low-end computers to run. But flat artwork displays on an exponentially greater amount of hardware without skimping on visual charm. Bandit camps dotted forests and meadows. Towering structures such as Candlekeep library seemed to loom over characters. Skeletons, goblins, and worse prowled gloomy dungeons.

"They were taking graphics to a different level,” Parker said of the BioWare team. “To me, it was inspiring just to work on a title that was like that: A title where we were trying to create a living, breathing world."

James Ohlen endeavored to extend the game’s sense of place through its user interface. As a tabletop gamer for over half his life, he understood the tools that players would need access to as they played: inventory screens, character stats, the health of his party, a map of the dungeon, town, or road players were traveling. For reference, he looked to a set of recent computer games highly regarded for their simplicity—and, to the detriment of BioWare’s developers, their addictive qualities.

"We all played so much WarCraft, StarCraft, and Diablo that I'm sure Baldur’s Gate would have come out several months earlier without [the team spending so much time on] those games," Ohlen admitted, laughing.

WarCraft developer Blizzard Entertainment and Diablo developer Blizzard North had collectively garnered a reputation for accessibility. Their games were designed so that anyone, even a newcomer to computers, could take up a mouse and understand how to play within seconds. Every action in Diablo could be performed with a mouse.

WarCraft II and StarCraft operated similarly. The UI was minimal: Buttons to move, attack, patrol, build, or repair structures appeared only when players clicked on a character or building able to perform those tasks. In contrast, the Gold Box RPGs of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s were either plain and drab, their interfaces often difficult to decipher as a result of the rudimentary tools and graphics modes that had been available.

Character creation should be fun, but the Gold Box games built a mountain of words between players and starting their adventure. Making a single character could take hours as players puzzled out rules and calculated stats. "We were very cognizant to the fact that Dungeons & Dragons is, in and of itself, sort of a barrier to entry,” Parker remembered. “That maybe people played some Dungeons & Dragons, but probably all of these rules—THACO [To Hit Armor Class 0], all of that crazy stuff—made it hard for people to understand and play. WarCraft II had these controls that were pretty in-depth. We were like, ‘Okay, we can use those.’ I think the interface was discussed more than anything else.”

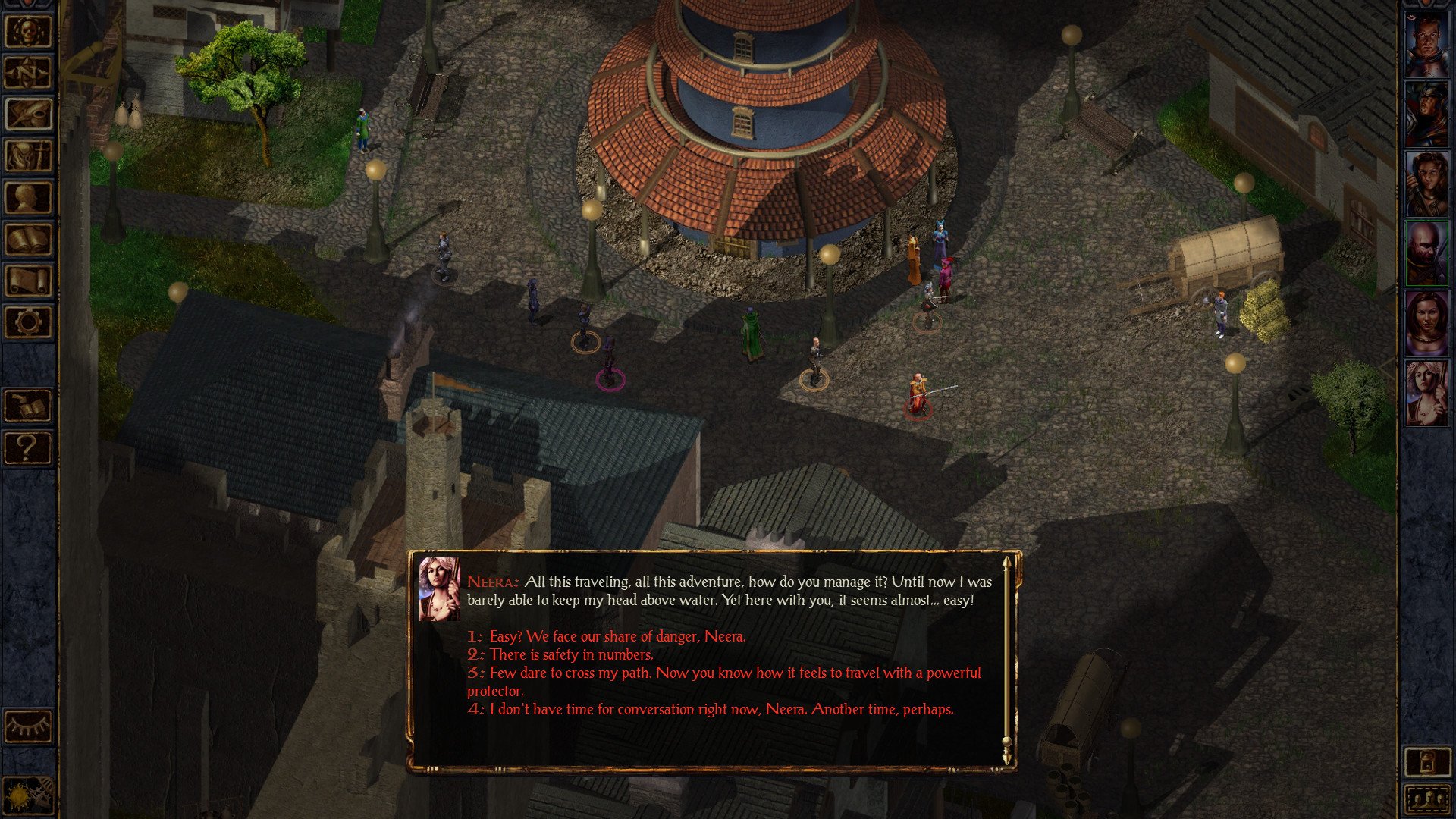

Baldur’s Gate interface resembles a Monopoly board. Bars of buttons show iconography that communicates function border the gameplay screen like a horseshoe. "I was more in favor of the game screen being in the top-left and the interface being at the bottom,” said Parker. “Ray [Muzyka] wanted the interface around all four sides. As he put it, he wanted to 'Look through his interface down onto the world.' After various discussions and concepts, we finally found an interface that was sort of a U-shape."

Actions are spread across three bars so players come to associate each row of icons with related actions. The bar on the left side of the screen lets players open their inventory, map, a journal that tracks quest progress and papers they find as they explore, and spell books. On the opposite side of the screen are portraits of each character in the player’s party. Those portraits display each character’s health, the order in which they attack during battle, and effects such as sickness or curses.

The bar along the bottom is context sensitive, similar to the UI found in WarCraft II and StarCraft. When players select a single character, the bar shows actions specific to that character. Selecting two or more changes the UI so that players can change the group’s battle formation, talk amongst their party, or even attack allies.

For the inexperienced developers building Baldur’s Gate, looking to some of their favorite games for inspiration was an invaluable resource. Ohlen is proud of the way the game’s UI marries the necessary functions of a Dungeons & Dragons session with user-friendliness. "If you're a D&D fan, you feel like you're playing Dungeons & Dragons, but at the same time it felt like a modern game. It was comparable to WarCraft and Diablo in terms of the smoothness of the interface, the responsiveness. It felt like a more modern game in that regard."

Little Movies

TSR and Wizards of the Coast had stayed on top of Dungeons & Dragons’ rules, updating by talking with players and keeping tabs on trends in tabletop gaming. Beginning in 1987, a small team at TSR revamped the game’s rules and branded them Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition.

Many of the rule changes were made in response to pressure from media and the public. As Dungeons & Dragons had grown more popular, parents and religious groups had taken issue with the game’s use of demons and devils. TSR’s designers renamed them tanar'ri and baatezu, respectively, and tried to steer players away from morally ambiguous roles such as the assassin by emphasizing heroic deeds and quests.

For BioWare and Black Isle, the most important alterations in 2nd Edition concerned mechanics, such as the minimum number players had to role in order to hit a target. 2nd Edition also codified rules for multi-class characters, guidelines that the team transplanted in their game. The classes players could combine depended on the race they selected. Human characters cannot multi-class at all, while elves may triple down as, say, a fighter, mage, and thief. The cardinal rules of multi-class characters state they can only wield weapons of the latter class—so a cleric-fighter hybrid can only equip fighter-friendly implements. Additionally, multi-class characters earn the same amount of experience points as their single-class counterparts, meaning players who wish to access their hybrid’s best abilities should to spend points carefully.

Some spells, items, and rules did not translate well from pen-and-paper to PC game. D&D’s charm spell gives the caster complete control over his or her target providing the spell successfully takes hold. However, charmed characters can ignore some commands, such as a player telling a charmed player to kill their own character.

"The charm spell, I think, is probably everybody's favorite because there was just no way to do a charm spell in a computer game at that time, so we just turned it into a complete takeover of a character, which also probably made it the most powerful first level Dungeons & Dragons spell ever,” Parker said of the Baldur’s Gate variation. “Maybe not the most balanced,” he continued after a moment’s thought. “I think our goal was just to kind of layer it: Make it accessible so that people can get into it, but proudly state, 'This is Dungeons & Dragons. Here's all the spells. Even though you're probably never going to want to use half of them, we've given them to you.'”

"The reason we said we ‘modified’ the rules was because it wasn't a turn-based game, so we had to make some changes in order for it to work in a real-time,” Ohlen added.

Ohlen and Ray Muzyka butted heads over combat in Baldur’s Gate. Muzyka loved the Gold Box games because they had been predicated on turn-based combat, just like Dungeons & Dragons tabletop games. Turn-based systems allowed players to think through their moves before taking action. Ohlen appreciated the classics, but insisted that turn-based play was outmoded. Real-time strategy titles such as WarCraft II and Diablo proved that the future of gaming lay in fast, think-on-your-feet tactics.

They reached a compromise. Baldur’s Gate would play out in real-time, but players could pause the action during fights to take stock of their situation and queue up orders for their party to carry out when the action resumed. "You got the finer control of turn-based, but at the same time, you got the kind of exciting action of a real-time [strategy game]," Ohlen said.

Ohlen took to real-time-with-pause gameplay right away. When he encountered a group of enemies, he would maneuver his party into position, pause, and set up spells. When he unpaused, all of his actions would play out: characters moved, fireballs and lightning bolts scorched and zapped, swords clash, screams pierced the air, and enemy bodies dropping to the ground.

"It was like I'd get to watch a little movie go off, see how my strategy fell into place. There'd be epic music in the background," Ohlen remembered. "I think it worked out pretty well because it was different from turn-based games like Fallout 1 and 2, and from the RTS games that Blizzard was putting out."

Blending real-time and turn-based combat required BioWare’s developers—and their players—to rethink how they approached battle. That change in mindset mirrored how Ohlen presided over D&D games as dungeon master. Before an encounter, he would give his players ample time to prep. Fighters would scout enemy mobs and equip their best weapons. Wizards would ready their main spells as well as contingency spells in case their first attack wasn’t enough to put a monster down for the count. Ohlen’s role was to anticipate what they might do and prepare a Plan A and B of his own so that players wouldn’t grow bored by defeating every mob of enemies in their first attempt and without a hitch.

"That was kind of the way Baldur’s Gate was designed to be played: You set up strategies and tactics, unpause to see how they unfolded, and as soon as it started going poorly, you'd pause again and re-evaluate to decide what you could do in the moment to change how the battle is unfolding,” he explained. “Much like every innovation in the industry, none of this was planned out from the very beginning. This all came about through iteration and play testing. I loved that style of gameplay because it felt cinematic."

What Ohlen enjoyed most about real-time-with-pause action was how it added a layer of depth that existed more in the minds of players than in the game’s code. The thrill they experienced when a complex plan worked, especially if a battle had gone went sideways and forced them to pivot yet again, made players believe they’d gotten one over on the game. It had been out to get them, but they’d out-thought it.

"It wasn't really that you were brilliant,” Ohlen said. You just thought things through: If I do this ability, that ability, and then this other ability, maybe I'll win. And you often would win. It made the game feel a lot more balanced than it actually was."

Power and Story

As a dungeon master, Ohlen had learned to cater to a diverse range of tastes. “I learned that there are people who are into the story, and then there are the people who are into the tactics and the rules,” he explained. “You have to keep both of them engaged. You can give the story folks more interested in rules, tactics, and leveling up, and you can get the people who are rules focused more interested in the story. All players enjoy all of that. They enjoy both aspects, the power gaming and the story.”

BioWare’s team viewed Baldur’s Gate as both a foray into tactical combat and a story players could invest and see themselves in. As such, the game’s plot and the path through the world were developed in tandem.

One of Ohlen’s goals as lead designer was to inject Baldur’s Gate with a degree of player agency. Some players would be ensnared in the story right away and charge through it, eager to find out what happened next. Others would want to stop and smell the Belladonnas. "A lot of the best game designers in roleplaying games are dungeon masters, simply because being a dungeon master forces you to create worlds and scenarios where players feel that they have control and agency, but at the same time, you need to have a story through-line that makes them feel like they're part of something epic,” he explained.

Players assume the role of an orphan and ward to Gorion, a mage. They live in Candlekeep, a fortress of stone that houses one of the Forgotten Realms’ most prodigious libraries. Gorion is ordered by the ward to flee with him into the night, only to be stopped by an armored stranger who kills Gorion as he attempts to protect his ward. Players escape and begin a story told over eight chapters.

The Forgotten Realms was vast, and Baldur’s Gate would only allow players to explore a slice of it. Even so, that slice was an order of magnitude larger and more intimidating than anything they had made for Shattered Steel. They started small, building a tiny church that consisted of an interior room and one piece of a town. Chris Parker recalled seeing a prototype at Gen Con, an annual gaming and comic convention. "Candlekeep was one of the very first things that was built. It was empty, and there was very little to do there," Parker remembered.

Content trickled in. Players could leave Candlekeep and explore the surrounding wilderness. A few monsters patrolled areas. More were added as artists and programmers brought them online. Every week or so, large chunks of the game were plugged in. The developers focused on fleshing out the main path first by building areas important to the story. Sometimes they sprinkled in characters, monsters, and quests as they worked. Other times they backtracked and added color to regions later.

The Infinity Engine’s flexibility came in handy. Four months out from launching Baldur’s Gate, Interplay’s QA testers opined that many areas in the world felt empty. The game was solid in terms of bugs and glitches, but was lacking in things to see, do, talk with, and kill. For the last two months, BioWare’s team made a big push, churning out more characters, items, and quests for players to undertake using the tools Greig had crafted.

"That created a big headache for everybody because it added testing to the game, but I think it was really remarkable that they were able to go through and put that much stuff into the game that quickly," Parker said.

Although Ohlen felt energized enough to build the entirety of Baldur’s Gate on his own, he abided by Muzyka’s “trust, but verify” philosophy by handing many duties to his design team. Designers got a chance to flex their creative muscle by writing companions who players meet as they travel through the game. "You wanted to get that feeling that you were in a party, a D&D party. That was important because Dungeons & Dragons is all about having a party of characters,” said Ohlen.

Up to five companions can join the player’s party. Each comes with his or her own motivations and goals. That was another component of a successful Dungeons & Dragons campaign. Players invest in their characters, but they should also appreciate the combat options and personal backgrounds that other characters bring to the table.

While several designers wrote dialogue and quests for companions, the names of the companions as well as certain traits came from characters Ohlen’s friends had played in his old campaigns. "One of the Beamdog founders, Cameron Tofer, his character's name was Minsc,” Ohlen said. “[Cameron] was new to D&D, and a ranger, and a player who didn't take things seriously."

Lukas “Luke” Kristjanson was the designer who inherited Minsc while Cameron Stofer assisted on the Infinity Engine. Tan and brawny, Minsc catches the player’s attention when he asks for help rescuing a witch, Dynaheir, who was captured by trolls. Both Minsc and Dynaheir are available to fight alongside players for a time. After Dynaheir is eventually killed, Minsc pledges his services to players as he seeks out justice for his friend’s death.

Minsc’s pursuit of justice defines the character, as does his demeanor. Kristjanson wrote the ranger as physically powerful and intimidating to his enemies, but a gentle giant to his friends. Minsc engages in some of the game’s most humorous banter, inspired by the writer’s love of The Tick animated series, according to Ohlen. Some of Minsc’s best banter takes place between himself and Boo, his pet hamster. Minsc boasts of Boo’s otherworldly abilities as a “miniature giant” space hamster, even though the rodent is, in fact, an ordinary pet.

Years earlier, Tofer had roleplayed Minsc as if Boo were a legitimate threat, and had insisted that his fellow party members take the miniature-giant space hamster seriously. Kristjanson adjusted Minsc’s dialogue based in part on the hilarious improvisations of his voice actor.

Another companion in Baldur’s Gate, Edwin Odesseiron, had been created by another of Ohlen’s friends. A conjurer who falls under the “lawful evil” alignment of Dungeons & Dragons—one who exploits societal systems and morals according to rules—Edwin was roleplayed by Ohlen’s friend as a serious and sinister figure. On a lark, Kristjanson wrote a segment of Baldur’s Gate: Throne of Bhaal—an add-on pack for Baldur’s Gate II—that saw Elminster, Ed Greenwood’s iconic avatar in the Forgotten Realms, transform Edwin into a barmaid.

"He'll still talk to me about that,” Ohlen said. “I say, ‘I couldn't control my writers. Luke wrote that.’ He says, ‘But you were his boss!’ I say, ‘I know. I was a good boss who let his employees run with what they thought was right.’"

Occasionally, Ohlen would have to ask writers to trim word counts. Baldur’s Gate emulated Dungeons & Dragons in several ways, one of which was its use of prose. Although the game boasted beautiful visual and sound direction, character dialogue and action was accompanied by descriptive text of the sort a dungeon master might read aloud to paint a picture for his or her players.

"What you write on a page takes ten seconds, but all the resources that have to go into that—modeling, texturing, voiceover, music, all the rest—suddenly that ten seconds of writing becomes tens of thousands of dollars of assets. There were different reasons for why we would do the cuts,” Ohlen explained.

Vindication

Every day at four p.m., Chris Parker phoned Ray Muzyka for an update on Baldur’s Gate. One conversation revolved around Black Isle’s request that BioWare add a multiplayer mode to further simulate playing Dungeons & Dragons in a computer game.

Later in 1998, BioWare’s leaders told Parker and Feargus Urquhart that implementing multiplayer over the Internet was too Herculean a task for a team—just over fifty strong—who’d never built an online game before. Plus, their coffers were running dry. They asked Interplay for more money. Urquhart and Parker agreed to put funding together if BioWare gave them something in return. "We gave them an increased budget that would be used to add multiplayer to the game. That added, of course, a bunch of different interface screens and QA needs, all this stuff that took us a lot of work to get done,” said Parker.

By late 1998, Parker was ready to call it a wrap. He’d put in over eighty hours of work a week for over a year—over one hundred per week near the end of the project—bouncing between Black Isle Studios and BioWare where the development team was working just as diligently. "I actually never questioned how successful Baldur’s Gate was going to be. I certainly questioned when it would be done, but I never questioned how groundbreaking it would be,” Parker said.

Parker had had his hands full. When Interplay’s marketing and sales teams expressed no interest in creating a website for the game, he did it himself using web development suite Adobe Dreamweaver. He built the site by culling artwork that BioWare’s managers had sent him and combining it with an overview of the game’s story, game mechanics, and graphics. He had not written a single line of web code in his life before then.

When he delivered the readymade page to the marketing team’s web developers, they complained. It would take them at least two weeks to set the website live due to its complexity. "That was never seen as a wasted effort to me, or overkill,” Parker said. “I always thought, Everything I do for this project is important. It matters because this game is going to be really, really huge."

At ten p.m. one night mere days before Baldur’s Gate was due to go gold, Parker received an urgent bug report on his computer. Drizzt Do’Urden, arguably the most famous Forgotten Realms character ever, was dead.

Parker rushed to Urquhart’s office to explain the situation. Drizzt could be found and engaged in combat in one of Baldur’s Gate’s areas, but killing him was next to impossible—this according to the game tester who had pulled off the feat and filed his report. Parker was hoping Urquhart would tell him that it was no big deal. That they could roll out a patch to make Drizzt even closer to invincible after the game had shipped, rather than delay manufacturing of the gold master disc.

Urquhart asked Parker if he was really comfortable leaving the task for later. Parker sighed and went back to his office to phone Muzyka.

"The time difference between Edmonton to California is two hours,” Parker said. “I called Ray at one o'clock in the morning and said, 'Hey, I need to get this bug fixed.'"

As soon as Muzyka got off the phone with Parker, he called Ohlen at home and told him to go to the office and address the issue. "I think I'd gone in and it wasn't a big deal anymore, because it was really hard to do it,” Ohlen recalled. “We just convinced [Black Isle] it wasn't a big deal, though we didn't make killing Drizzt impossible. All I know is that it nearly broke me. I'd been working so hard and thought I was finally done, and that we were going to ship, and then I got the phone call. Goddamn Drizzt. I wanted to kill him."

Nearly two years of scrambling, increased budgeting, website design, character writing, and meticulous attention to details such as the game’s user interface—over ninety people-years of work—paid off when Baldur’s Gate shipped to stores in December. The game sold 175,000 units over its first two weeks, and was crowned the number-one-selling title according to several retailers in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and France—more than recouping its development costs and proving Black Isle’s faith in BioWare.

"I see that there are so many ways to do an RPG, and it ends up being about what works at the time," said Urquhart. "I do think that because we had more colors, more performance, more memory—we had more of these things, so ultimately, what Fallout, Baldur’s Gate, and Diablo were doing was they were more able to put people in a world that looked like an actual world. I'm not saying that Baldur’s Gate and Fallout were at the forefront of graphics technology at the time, but they were moving forward on getting people into a world, and then representing that world in different ways: in terms of dialogue, characters, voiceover, and things like that, which you just didn't see as much before that."

"The thing I enjoyed most, really, was working with BioWare," Parker said of the project. "They didn't know how to make such a big game either, and I didn't know how to make it. We were collectively working together just trying to make something that was really awesome. I was up there a lot, and we were all super friendly. I think in general, we always recognized that for all the work we were taking on, the only thing we cared about was making an awesome game. I can't work eighty to one hundred hours in a week anymore. I'd just fall over. But back then, I was ready to go. I worked really hard on it, and I knew BioWare was working every bit as hard as I was. That camaraderie was just amazing. I think what I learned on that title, just making a roleplaying game in general, both failures and successes, is anything I could have learned anywhere else."

"I was proudest that I was a member of the team that brought Dungeons & Dragons to millions of people who otherwise may not have experienced it, being a part of a time in the industry when there was a lot of openness to what could happen, how games could be made, and making a game that represented D&D,” said James Ohlen. “That was my passion. It still is."

Temperance

BioWare co-founder Augustine Yip was proud of how Baldur’s Gate turned out, but had returned to medicine shortly before it launched, leaving BioWare in the hands of Ray Muzyka and Greg Zeschuk.

Talk turned to what the studio would work on next. Baldur’s Gate II was a given for many members of the team. Others proposed alternatives. "There's always been a struggle within BioWare. There have been a lot of people who don't just want to do RPGs, and then there are the big Dungeons & Dragons nerds who just want to do RPGs," said Ohlen. "I think that struggle has been beneficial, and has created problems, but the beneficial part has been that we've always been a company that never wants to rest on our laurels. We're always trying to push things forward because it was a culture that said, ‘I don't want to keep making the same game over and over again.’ That just isn't part of the DNA of the company."

Zeschuk indulged his interest in creating other types of games with MDK 2, an action game that received praise for its gameplay, level design, boss fights, and graphics. As for Ohlen, he knew exactly what he wanted to do. Over the next two years, he resumed working one-hundred-hour weeks on Baldur’s Gate II. The game was developed by BioWare’s largest team to date. Over nearly two years, the developers packed in more characters, locations, stories, and opportunities for roleplaying, including romantic relationships between characters, a staple of BioWare’s roleplaying games going forward.

Baldur’s Gate II raked in $4 million in sales over its first two weeks in stores in September 2000. Six months and 3.5 million sales later, Black Isle Studios and BioWare announced development of an add-on pack to be published later in 2001. James Ohlen was proud of the franchise’s success so far, although he knew he was running his team into the ground. If he didn’t ease off the gas a bit, he might return to the days when he worked with people who half-jokingly threatened to break bones.

"I had my designers revolt at the end, because I said, ‘The game’s not big enough,’ and they said, ‘It is big enough,’” he said of work on Baldur’s Gate II. “If you've played it, you know it's big enough, but I said, ‘No, we're going to do this plot where you go back in time and change the timeline, and then there will be this alternate timeline version where the Sword Coast is under oppression and you have to free it to save the timeline.’ Everyone said, ‘You've lost your mind.’"

Ohlen became aware of the depth of his team’s exhaustion a few months after Baldur’s Gate II went on sale. When Ray Muzyka called him into his office one afternoon, Ohlen braced for his mentor to heap praise upon him. The game was selling in the millions. Instead Muzyka, in his customary serious demeanor, gently chided Ohlen for letting the sequel’s development schedule slip by a month.

Ohlen was stunned. "I was like, ‘Huh? Wha?’ He was talking about how I'd gone crazy with the scope, which was true. It could probably have been a little bit leaner, and I had driven the team hard," he admitted.

Since starting at BioWare, Ohlen had never lorded his work schedule over his peers. It was something he did, that was all. But his meeting with Muzyka helped him concretize his understanding of the position he held. “I got so much autonomy, and it was a dream job, but I knew that writers and designers didn't have that degree of autonomy may not have my level of love or dedication. It's important to understand the power you have as a boss. If you guilt people, that's almost as bad as asking them to do it.”

Before announcing his retirement from game development in July 2018, James Ohlen directed a number of bestselling roleplaying games at BioWare. Some, such as Neverwinter Nights and Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, were based on licenses owned by external companies, but their gameplay and stories resonated with millions of players thanks to the team’s aptitude for merging storytelling and intricate gameplay systems. Others, such as the Mass Effect and Dragon Age franchises, were homegrown properties carefully cultivated by teams which number in the hundreds of employees.

Ohlen cited Muzyka and Zeschuk, who had retired a few years earlier after Electronic Arts acquired BioWare, for giving him a collective example on which to model his extraordinary career. “Ray and Greg gave you the freedom to do what you wanted, and they weren't micromanagers at all, but they wouldn't hide from giving critical feedback to their people. It fostered a culture where people trusted each other enough to give and take critical feedback."